Economic prosperity is more threatened by Climate Change than we used to think

Evolution of economic damage models for Climate change.

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function."- Albert Allen Bartlett (Physicist)

We inhabit a planet experiencing dramatically different environmental conditions than our ancestors did going back many, many generations. That would be true even if all planet-warming emissions came to a sudden and abrupt stop tomorrow (which they won’t). The purpose of this essay is to show how the economic systems we rely on and the people who run them are badly underestimating the impact of climate damage on our collective prosperity.

Damage functions and Nordhaus work

Economists are fond of deploying mathematical functions to support their arguments. Finding relationships between quantifiable variables is the heart of the work of econometrics, a hammer in the economist’s toolbox that over time has started to treat every question as a nail.

As such, if asked to investigate the economic consequences of climate change, most economists would turn to some sort of mathematical expression they could plug in available data into to generate an answer. These are known as “damage functions”. For his efforts in this line of work, William Nordhaus won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2018. Nordhaus’ Dynamic Integrated Model of Climate and the Economy (DICE) informed US policymaking in the previous decade, by providing an estimate of how much incremental increases in global temperature could be expected to lead to reduced future provision of goods or services or “damage” to economic output.

If the Nobel prize was awarded in recognition of the influence of Nordhaus’ work, in hindsight it also throws a spotlight on the dire over-simplification of early damage functions. To be clear, economists often use simplifying assumptions as part of their work. The real world is messy and complicated: to conclude anything in economics requires making certain simplifying assumptions about the variables you are working with. Further, economics as a discipline command outsized influence over political leadership and policymakers. So, if presented with opposing viewpoints between an economist and a climate scientist, when it comes to shaping policy, the economist’s word is more likely to win out. That’s why it is so crucial that economic models estimating the impact from climate hazards to key variables like GDP growth get it right.

Damage functions have evolved over time. From Nordhaus’ early work to the present, economists are incorporating far more natural variables, as climate science itself has improved in the intervening years. Beyond the impact from changes in average temperature, more recent models also incorporate factors like variability in temperature, more detailed information on rainfall, as well as long-term impact from climate-related shocks.

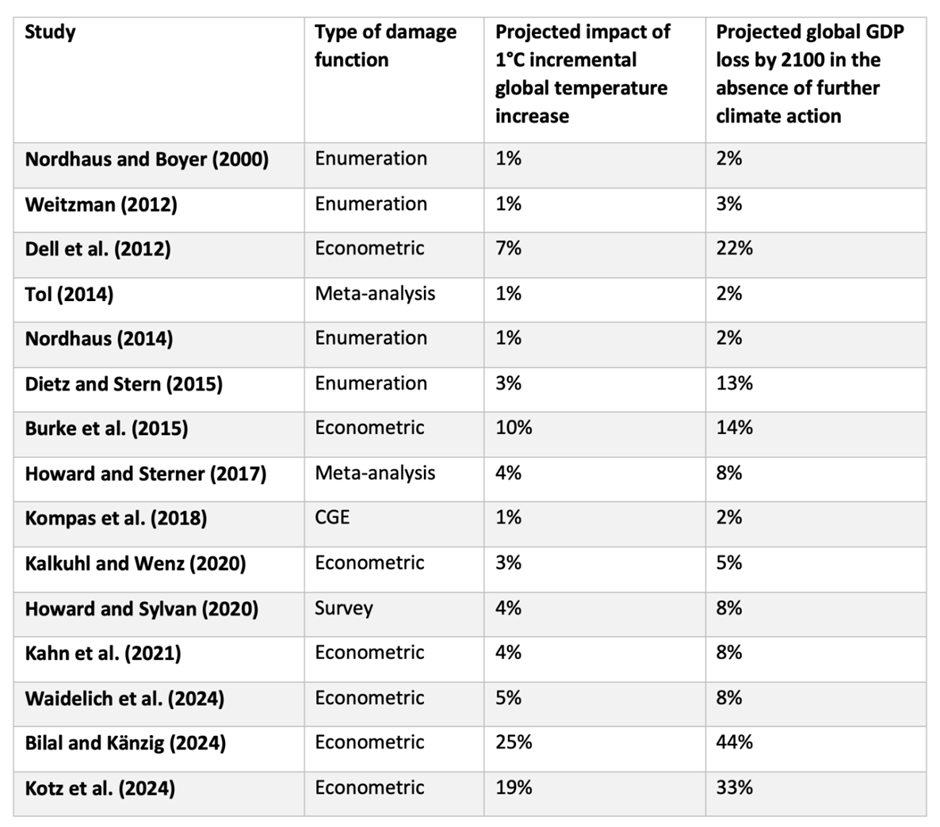

Damage functions are primarily classified under two approaches-enumeration and econometric. In the first approach, all possible channels through which climate change damages the economy are listed, impacts are quantified at various warming levels and summed up to obtain an aggregate. In the second approach, panel regression models are used to estimate economic losses although they are criticized for capturing only short-term weather dynamics. Nordhaus used the enumeration approach while recent studies use the econometric approach. The results of these studies are summarized in the table below.

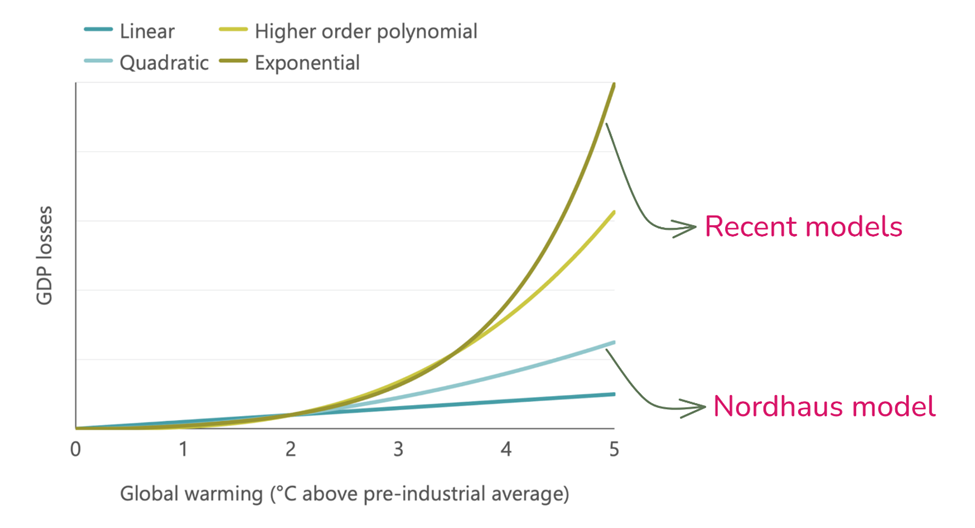

With each passing study, the damage predictions are ramped up to capture the worsening impacts from climate change. This is reflected in the evolution of the type of mathematical functions used in damage modelling. From the gently sloping quadratic functions of Nordhaus’ earlier damage estimates, we now see more exponential functions of climate change-driven economic damage as illustrated below.

Some of the sharpest criticism of Nordhaus’ work comes from Australian economist Steve Keen, who decries assumptions like considering 90% of world GDP is unlikely to be affected by climate change “because it takes place indoors” and failing to account for discontinuities in the relationship between temperature and GDP in the future wrought by climate disruption. A larger point that Keen makes is that economics has not sufficiently taken on board the concerns put forward by climate scientists, to the extent that damages from climate change may be at least an order of magnitude worse than forecast by economists.

Though Nordhaus and others have been looking at the interaction of climate change and the economy for many years now, this kind of analysis came into the mainstream relatively recently. The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a group of central banks and financial supervisors was formed only in 2017, to contribute to the development of environment and climate risk management in the financial sector among other objectives. The NGFS included the econometrics work by Kotz et al (2024) in its most recent modeling.

Underestimation of recent economic and physical risk models

Despite the inclusion of additional climate variables and exponential functions in recent studies, economic damage seems to be underestimated in most academic or open-source models. The primary reason for underestimation is that these models have blind spots on cascading impacts and tipping points (like melting of ice sheets in Antarctica, collapse of rainforest ecosystems etc). This observation is validated from the historical damage data not being reliable for extrapolation to predict near future damage losses.

A case in point is the recent LA wildfires in January 2025 which is the costliest blaze in US history. AccuWeather, a company that provides data on weather and its impact, puts the damage and economic losses at 250-275 billion dollars. To put this estimate in perspective, the average historical damage cost from wildfires in US (1980-2024 period) was 6.43 billion dollars and the highest single wildfire historical damage was 23 billion dollars from the western California wildfires in 2017. Both historical damage costs are accounted for inflation, coming from the publicly available dataset from National Oceanic and Atmospheric administration (NOAA), US. This shows an order in magnitude jump in the damage cost from wildfires in US, and plausibly for other extreme climate events as well. This highlights the urgent importance of the need to improve the current economic and physical risk models by accounting for non-linear impact from tipping points.

Looking back at the Covid-19 pandemic where the number of cases exponentially spiraled in a short period of time across the world causing immeasurable damage, it seems we as humans continue to fail to appreciate the exponential function and not act in accordance with it. The 2025 LA wildfires are another reminder for humans to take exponential surge in damage from extreme climate events more seriously, model them appropriately and act more proactively.

Economic costs of Climate change for India

India is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change. In a review of existing literature on how much climate change is likely to cost India in terms of economic growth in the years ahead, the London-based Overseas Development Institute (ODI) notes that differing methods throw up a wide range of estimated answers to this question.

With a 1°C increase in global temperatures, which we have already seen, one study projects a 3% of GDP cost for India every year, while a three-degree Celsius rise in global temperatures would cost India 10% of GDP every year. These estimates are based off looking at falling harvests, sea level rise and higher health spending. If global temperatures rise by 3°C, ODI reviewers estimate that India’s economy could be up to 90% smaller by the end of the century compared to a scenario without climate change. Remember, this is in comparison to a hypothetical world in which climate change is not taking place, effectively saying we could have had almost twice as big an economy in India by the end of the century were it not for the global temperature increase by 3°C.

Conclusion

Environmental economists have been hard at work making the case for why tackling climate change makes eminent economic sense and is in fact an extremely urgent imperative. Unfortunately, political challenges, deep vested interests, and some social and psychological barriers are preventing the scale of action we all would benefit from.

In this article we looked at the evolution of the economic loss models from a macro perspective. However, we found out that even the recent economic models underestimate the damage as they do not account for losses from tipping points, socio-economic risks like migration, armed conflict etc. We will look into this in detail in a future article.

Also, what does these models mean for us at an individual level particularly in India, where there is a strong drive in the urban middle class to seek more economic prosperity while dealing with harsh impacts from climate events? Can we do climate innovation to simultaneously grow GDP and address these impacts? How much national budget should be allocated to climate R&D for this to happen? These are the topics we will continue to explore on Climate Rubik.

Climate Rubik is a reader supported knowledge platform. We would really appreciate your monetary support (links below) if you enjoyed reading this post and found it insightful.

If you are interested to be a guest writer on this platform, do check out this page.

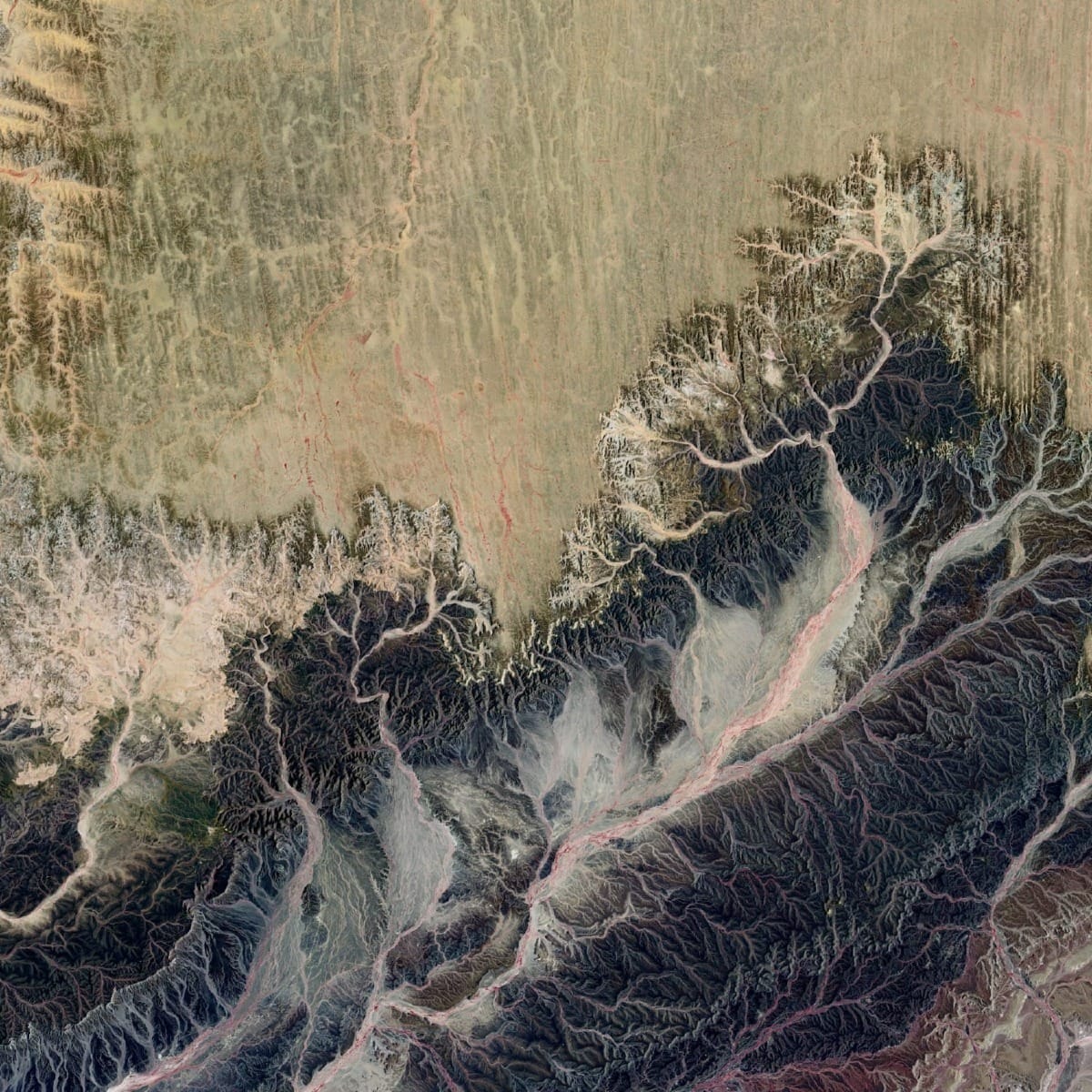

Cover image by USGS / Unsplash.

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0