Nuances to consider before becoming a Parent in an uncertain climate future

Climate lens on having kids.

There’s no straightforward answer when it comes to choosing if — or when — to have children.

For most of history, this wasn’t even a question: child-rearing was simply part of life. For many people, it still is, even as modernity and its cultural shifts have created space for individuals to live long, fulfilling lives without ever procreating. This is especially true in more individualistic societies, where the desires, ambitions, and agency of the individual are valued above the needs of the collective.

Yet millions are choosing to skip parenthood even in countries without a long cultural tradition of individualism, such as Japan, South Korea, and India. The reasons vary — from economic pressures to worsening gender relations.

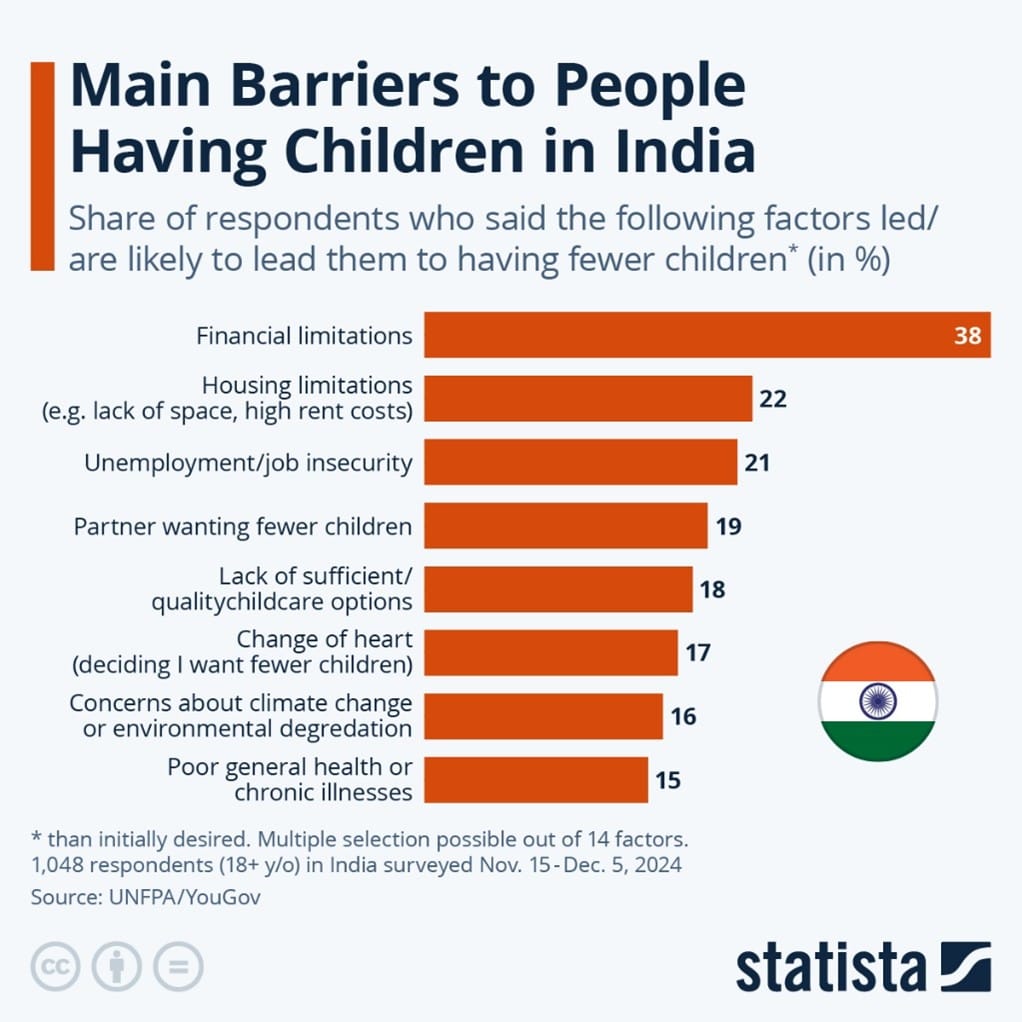

While it’s lower on the list compared to other factors, a 2024 survey of over 1,000 Indians found that climate change and environmental degradation are among the key reasons respondents are likely to have fewer children.

If someone is mentally, emotionally, and financially stable, it becomes imperative to think through the weighty decision of bringing a new life into the world in a responsible way. One aspect of that decision is having confidence that you can provide a good life for your child and that they will have the opportunity to live well over the course of their lifetime. The reality of climate change casts a shadow over anyone’s ability to have that confidence today.

A decade after the Paris Agreement, the global effort to secure a liveable future has faced major political setbacks and is under serious strain. This, in turn, slowed international progress on reducing emissions, a challenge now compounded by new, rapidly growing sources of energy demand from technologies like artificial intelligence, which, in contrast, enjoy strong political support.

As a result, climate scientists are clear that the Earth is headed for major increases in global temperature and far greater climate impacts in the years to come than humankind has experienced with the sub-1.5°C of warming so far.

“The last ten years have included all ten of the warmest years observed in the instrumental record,” according to non-profit Berkley Earth. This extreme warming has brought intense heatwaves across Asia, glacial-melt-driven flooding and landslides in the Himalayas and other high mountain ranges, and historically bad wildfires in places like Los Angeles, to name just a few recent examples.

Anyone deciding whether or not to have a child today faces a difficult choice. You could argue that starting a family has always been challenging, and there’s truth to that. In the past, for example, parents had to contend with the ever-present fear of nuclear Armageddon during the Cold War.

Yet we would make the case that deciding whether to have children today is a far trickier question both ethically as well as practically than it was then.

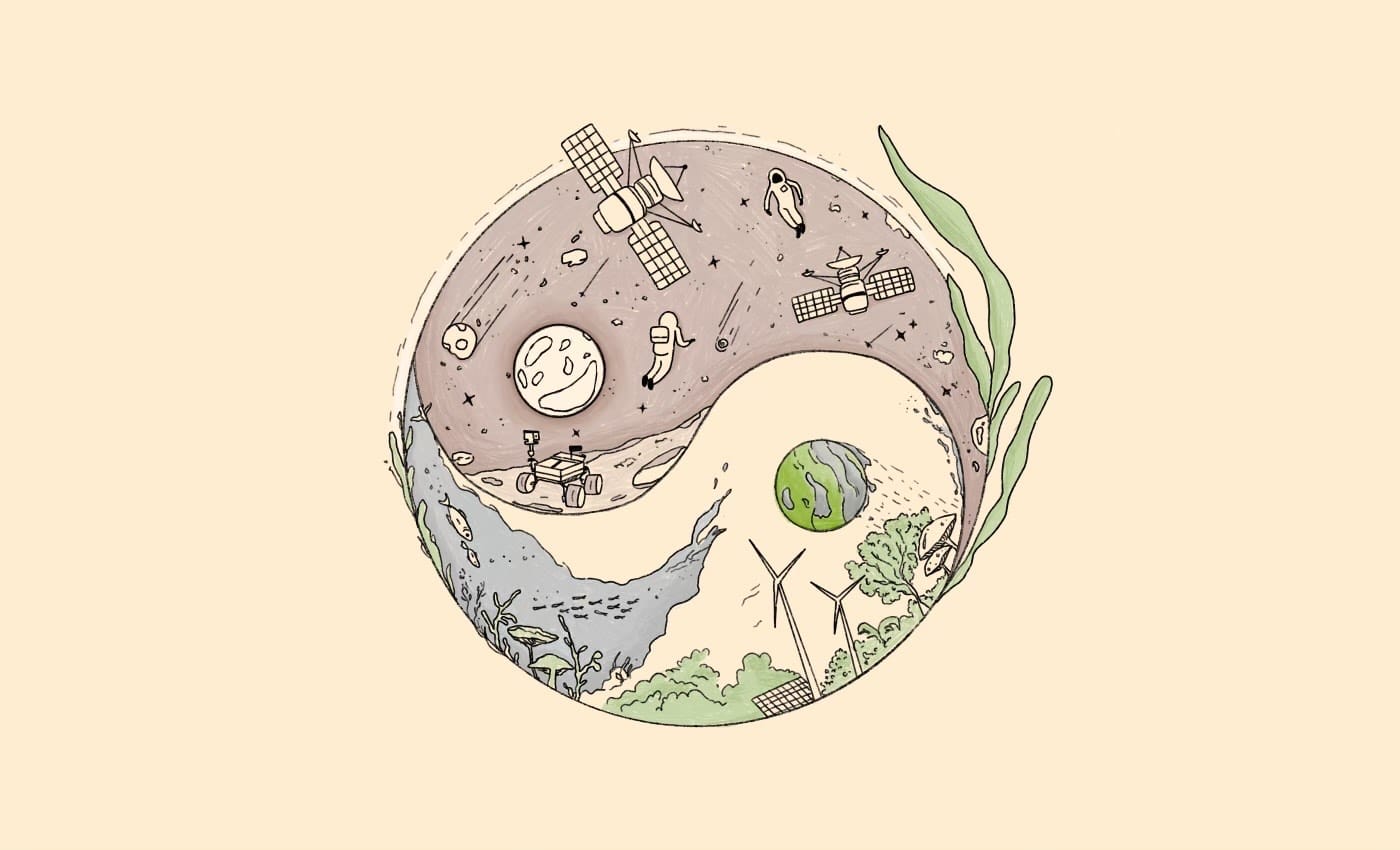

Climate change does not represent an instantaneous, cataclysmic end-of-the-world threat in the way nuclear war and mutually assured destruction once did (and still could). As alarming as the scientific projections are, it’s important to note that climate change does not mean the end of the world. Rather, it signals the end of life as we know it.

This shift in the ground beneath our feet (sometimes literally) will bring with it the collapse of various systems – financial, political, technological and social– that run the modern industrial society. Yet many of these disruptions will likely be gradual and influence each other in unpredictable ways. The negative impacts will land unevenly and at different times, depending on geography, economic class, and a host of local factors. In some small pockets, there may even be a few positive effects, especially for those with the foresight and resources to adapt. All of which make the decision around whether or not to have children trickier.

On the other hand, it’s conceivable that human action could throw the balance of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in our atmosphere so out of kilter as to permanently shut down the biosphere. That would take some doing, however, and progress made in various spheres, from renewable energy becoming affordable, to most major countries setting some kind of emissions control targets, and the rare example of a planetary boundary that humanity has managed to retreat from infringing (the ozone layer) all make it less likely.

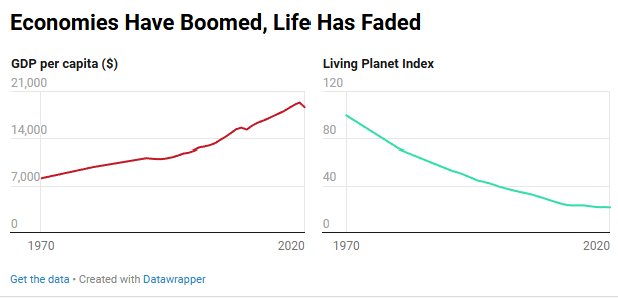

The limited progress we have made will not be enough to avoid dramatic ruptures in the systems that most of us, especially the global elite, have grown accustomed to over the last few decades. Without going into detail on the hard physical constraints of the global energy transition, it is sufficient to say that our modern civilization is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels. And as long as unceasing material economic growth remains the priority of nation-states everywhere, you can assume that, as a prospective parent, there will be limits to how far fossil fuels are phased out to mitigate climate change, even in the best-case scenarios.

The Moral dilemma of having kids in a warming world

A big part of your calculation around whether or not to have children in a climate changed world may revolve around determining if it would be a morally sound choice. Many climate-aware people in the affluent global elite are acutely aware of how their lifestyles contribute to the planetary crisis because of the emissions and natural resources required to maintain it. This can lead to a profound sense of guilt and shame.

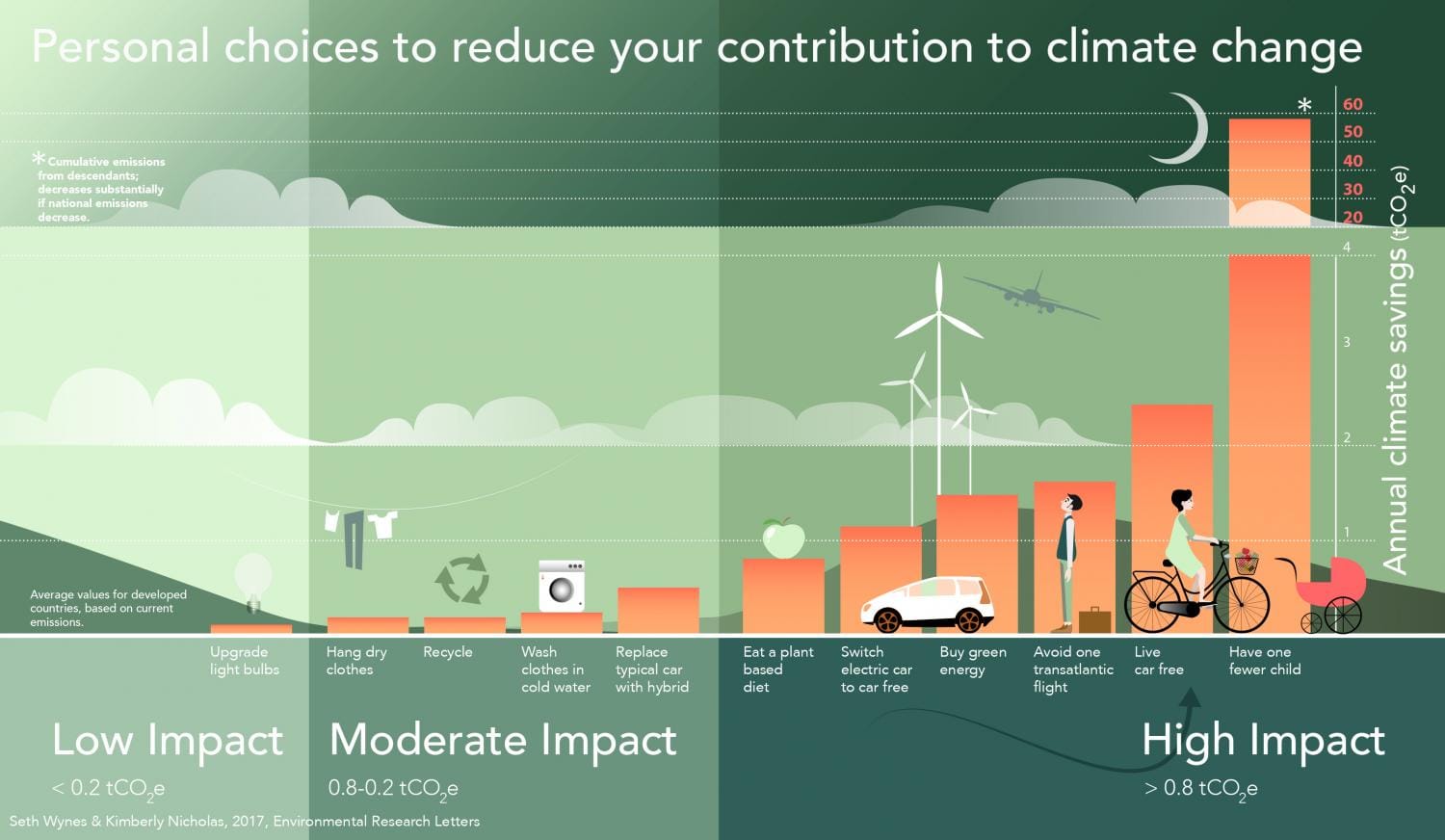

Bringing even one more person into the world, with the carbon footprint and resource use that come with raising a child, might feel like adding to the environmental burden you already create. But this is a well-intentioned yet skewed way of seeing the problem and our role in it as individuals, especially when we are not the ones running fossil-fuel giants or setting national energy policy.

Another school of thought is antinatalism, whose followers think human lives are intrinsically filled with suffering. For them, climate change is one more reason — one more string to the bow — for why people shouldn’t procreate on moral grounds.

Even without adopting an antinatalist stance, many people in the climate community choose not to have children because they don’t want to raise them in an increasingly degraded natural world.

At the same time, we explain why focusing only on the “carbon footprint” of one additional life is too narrow a view.

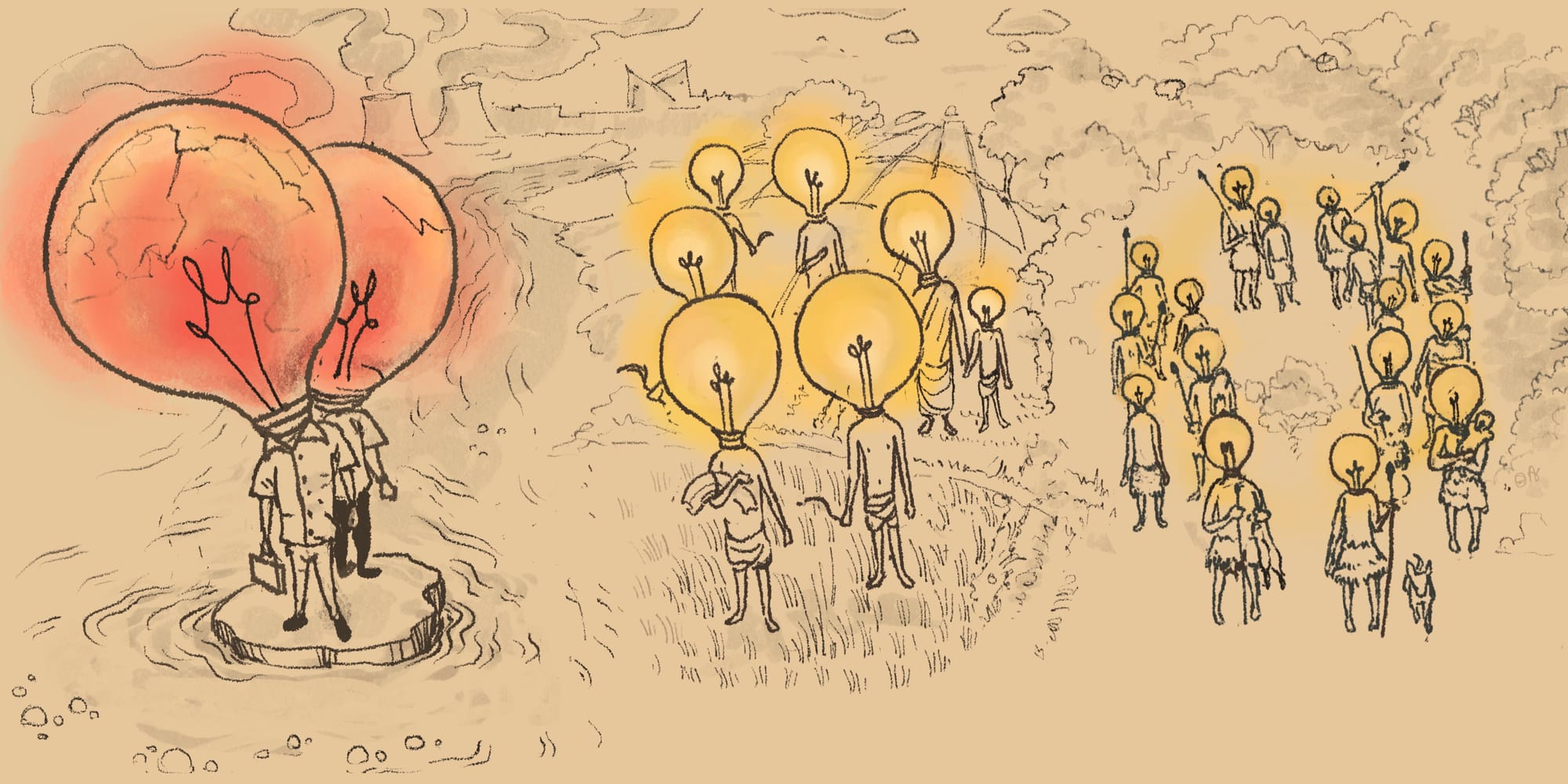

You are but one tiny human being. Among more than 8 billion. all of whom depend on a social and economic system built on the immense power of fossil fuels, a system whose everyday functioning is now reshaping the very planetary conditions that make life possible.

In an ideal world, your individual choices, whether in education, career, travel, transportation, or even having children, could meaningfully shift things in a positive direction, especially if another billion people shared your convictions and made similar changes. Unfortunately, the world we inhabit is far from ideal.

Doing “your bit” through lifestyle choices, like cycling, or using public transport, rather than a petrol- or diesel-fuelled car, or being vegetarian, is perfectly valid and may even offer some psychological benefits, aside from their inherent value. But on their own, such choices are not going to change what is playing out on a planetary scale. Neither will your choice to have children.

It’s far too narrow a view to focus only on the emissions that might result from fulfilling the natural desire to become a parent. Having children does not make you a bad person for contributing an infinitesimally small amount to the environmental impact created by our society as it is currently structured.

This sort of narrative framing has been pushed by insidious fossil-fuel communications strategists for decades to shift the “responsibility” for climate action onto ordinary people and away from powerful corporations, political leaders, and policymakers.

Focus on better, fairer questions

Rather than dwelling on the infinitesimally small contribution to global emissions that starting a family would involve, it’s far more important to consider whether you would be able to raise any potential children in a way that gives them the best possible chance not just to survive, but to lead fulfilling lives in the difficult times ahead.

It’s a hard question to answer. The best place to start is by thinking deeply about whether you have a personal climate action plan for handling those challenges, both for yourself and with any potential partner you might have children with. Such a plan should also consider several fundamental questions, like where the right place for you to live might be, and whether that place is likely to remain resilient as climate impacts worsen (which they will).

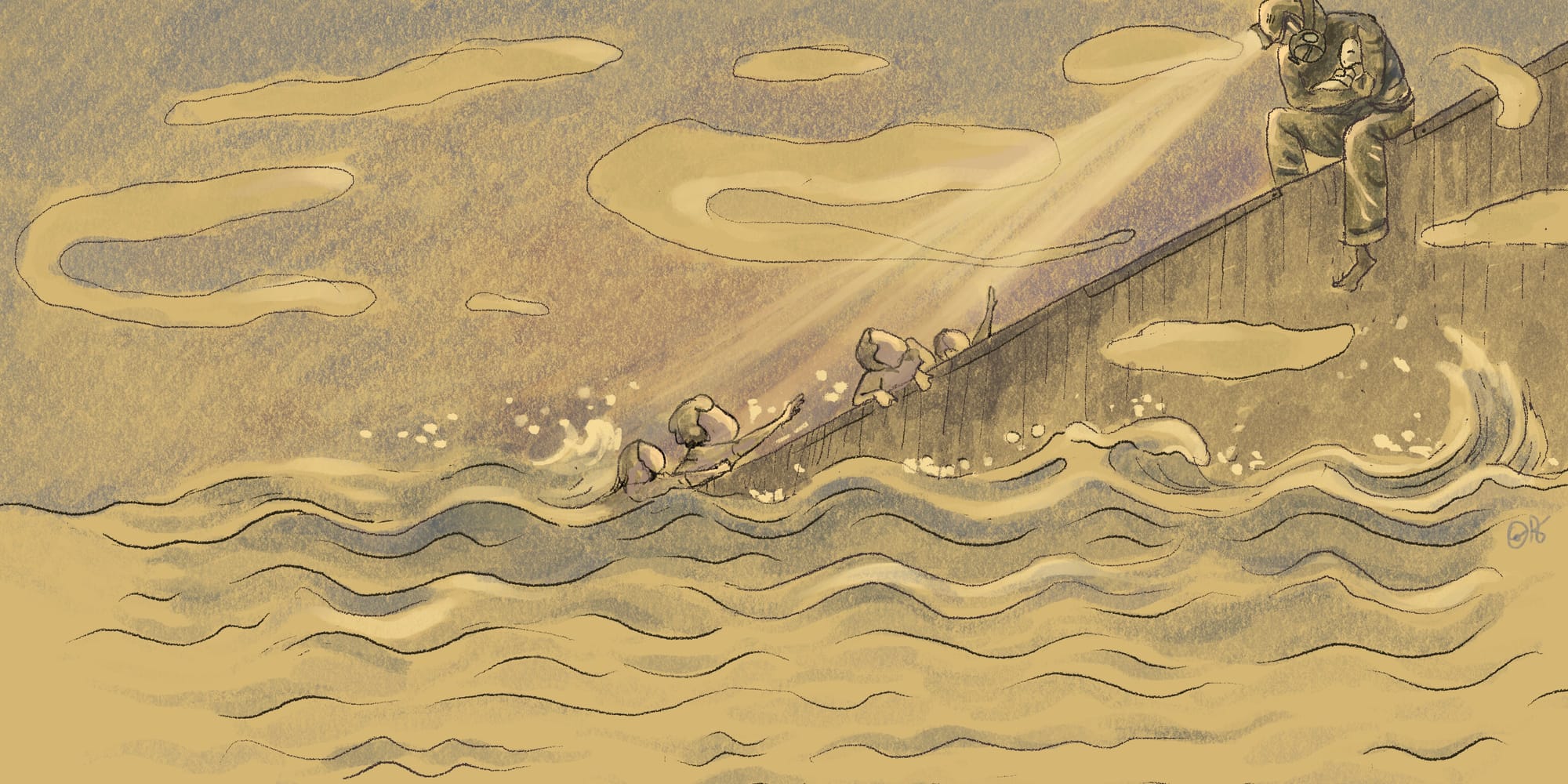

If finding the right place requires moving, what might be the best time for you to shift? We will all need to make many of these crucial decisions even amid a high degree of uncertainty. Many countries that were more open to immigration in previous decades are increasingly less so, despite pressures from aging populations, underlining how geopolitics deeply shape the options open to you at different points in time.

What kind of people would you live with if you become a climate migrant? What will you do to preserve your assets and continue to generate some form of wealth in these conditions?

Some trends — like the rise of remote work and the ability to build multiple income streams in the modern digital economy — may help. Others, such as job market disruptions from new technologies like AI or potential debt crises, may complicate your efforts. You may already understand the importance of earning money, but it’s equally important to consider how the way you manage that money contributes to your ability to build resilience in the face of climate change.

These are all essential, if initially unintuitive, questions to work through before arriving at a clear answer, one way or the other, on the deeply personal choice of whether to have children in the context of climate change.

Money can only take you so far

Having more money to manage the life transitions in your personal climate action plan can certainly help. But adapting effectively to climate-related disruptions will require far more than focusing only on your physical surroundings or material circumstances.

Today, a large enough bank balance can still buy access to thriving natural environments. That may not remain true for long, as biodiversity declines, natural habitats are cleared to fuel economic growth, and global financial assets continue to swell. It’s not hard to imagine a near-future where runaway climate change and environmental degradation make the mountain town you once visited on holiday either too expensive or too unwelcoming for outsiders, or where the house on the city’s edge with a view of green hills becomes both unaffordable and threatened by unchecked urbanization.

In that light, a large part of building resilience will come from adapting at the psychological, emotional, and even spiritual level. You may have had certain expectations for how life would unfold—expectations shaped by the assumption of a relatively stable society. But the unpredictable and varied disruptions ahead (what climate futurist Alex Steffen calls “discontinuities”) mean there may be a sharp gap between the future you once imagined, what you thought raising children would look like, and how reality ultimately unfolds.

Having a more realistic expectation set about what’s on the horizon – grounded in an understanding of what’s already there – can dramatically improve your capacity to make the right call on major personal life questions like the decision to become a parent or not to. In fact, it’s conceivable that someone living an elite, wealthy lifestyle in the current paradigm may find it a lot harder to adapt to the climate changed world we are heading into, because their expectations for how they wanted to raise children increasingly diverge from what turns out to be possible for them.

If you have children while just assuming climate change will be solved at some point by someone out there and raise those kids with that assumption, you might be in a very tight spot in a few years. Having kids as a climate aware person, with expectations closer to what the reality will be, is a very different proposition.

Final thoughts

Once you are making progress answering some of these questions, you may be ready to draft a climate action plan for your potential family. Of course, every parent wants their children to outlive them. So a family climate action plan should look further ahead than planning for just yourself or as a couple.

You don’t need perfect wording, but it helps to sketch what you would tell your child about climate change as they enter the age of reason. As a climate-aware parent, it would be your responsibility to help them prepare mentally, emotionally and physically for the risks ahead. This may sound daunting, which is why the decision to have children is trickier today than it has been for a long time.

One alternative is to adopt. Without weighing the full pros and cons here, adoption avoids some of the ethical dilemmas raised by bringing a new life into a world facing severe climate disruption. Adopting a child who already exists can be deeply beneficial for that child, especially if you are actively thinking about a family climate plan.

If, after considering the factors above, you decide not to have biological children, we hope this essay gives you a logical framework to explain your choice when questioned by family or others. At the same time, avoid demonizing or belittling those who do choose to procreate. As a child-free, climate-aware adult, you can still offer vital support and guidance to young parents and to friends navigating these issues.

If you ultimately decide to have children, do so with your eyes wide open. Life will intervene but prioritize developing a sound family climate action plan — and sooner rather than later. Your decision is valid; if anyone tries to shame you over it, we hope this essay helps you defend your reasoning. Bear in mind that the world your child grows up in will be very different from the world you and several past generations experienced. That should inform your parenting and place the onus on you to think proactively about how best to prepare your child, rather than relying on conventional wisdom that may no longer apply.

We would really appreciate your monetary support if you enjoyed reading this post and found it insightful.

PS: This article has been edited by Anjaly Raj.

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0