Dissecting higher order effects from industrial technologies

Delayed, cumulative, systemic effects from industrial technologies.

There are known knowns, and there are known unknowns. But there are also unknown unknowns- Donald Rumsfeld.

We are all familiar with the immediate, visible harms of socio-environmental problems such as air pollution or overpopulation. These are the direct or first-order effects. What we pay far less attention to are the higher-order effects — the second- and third-order consequences that emerge slowly, compound over time, and often become unmanageable or irreversible. In simpler terms, these are the unintended consequences of our actions. While higher-order effects can sometimes be positive, this article focuses on their negative forms: what they are, why they arise, and why understanding them is essential for addressing today’s major environmental challenges.

Many socio-environmental problems begin with the introduction of a new technology. Its creators focus on the market opportunity and overlook the risks. Society initially embraces the technology for its benefits, but over time the downsides begin to appear. The immediate, visible harms are first-order effects, while the delayed, cumulative, and systemic consequences that surface later are higher-order effects.

If we ask why risks and opportunities are not weighed equally in the early stages of a new technology, the answer lies in incentives. In a capitalist system, companies are rewarded for seizing opportunities quickly and gaining a first-mover advantage, not for slowing down to assess long-term risks. It is also mentally easier, and more profitable, to plan for growth than to plan for precaution. The same tendency applies at the individual level as well.

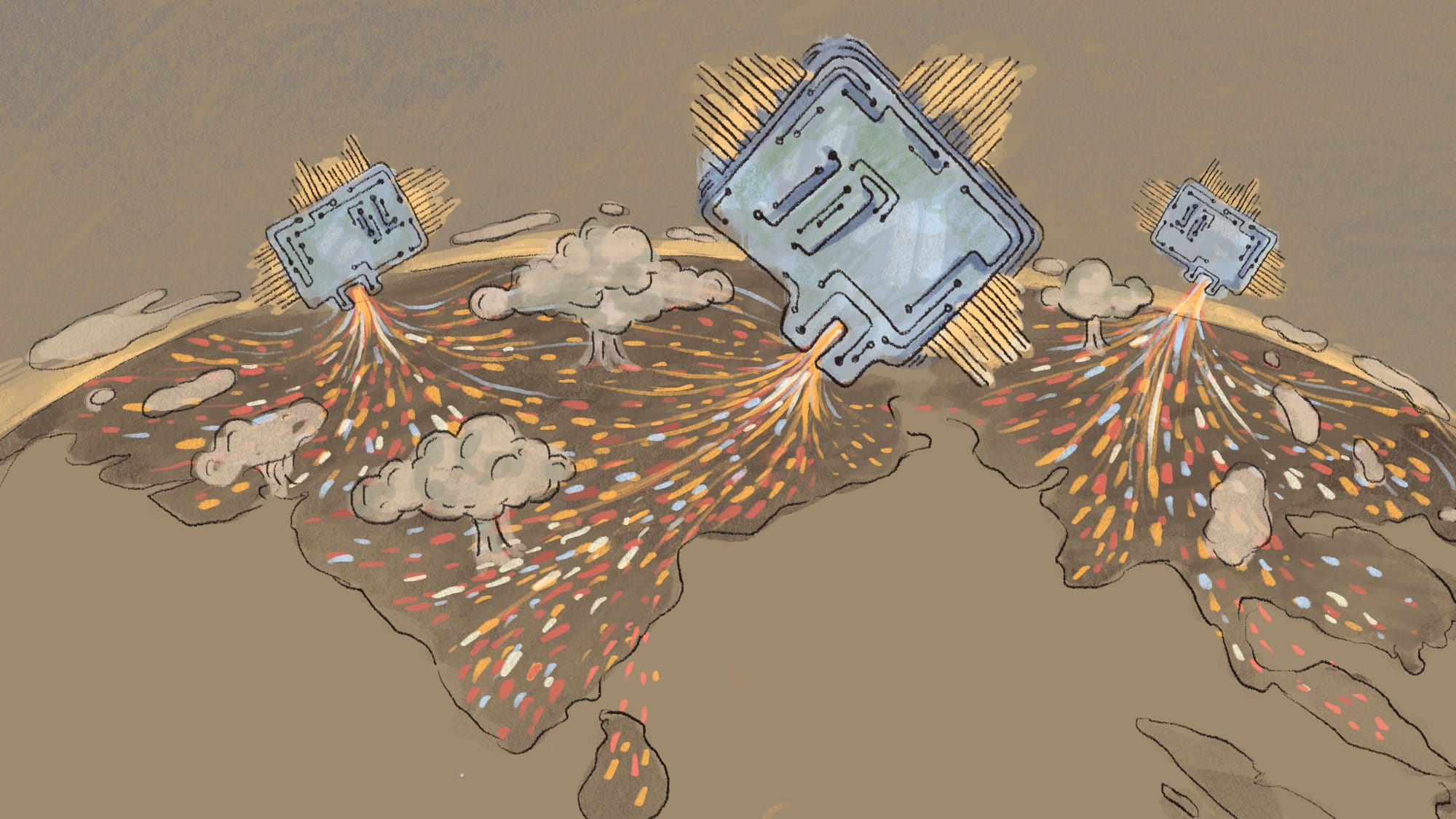

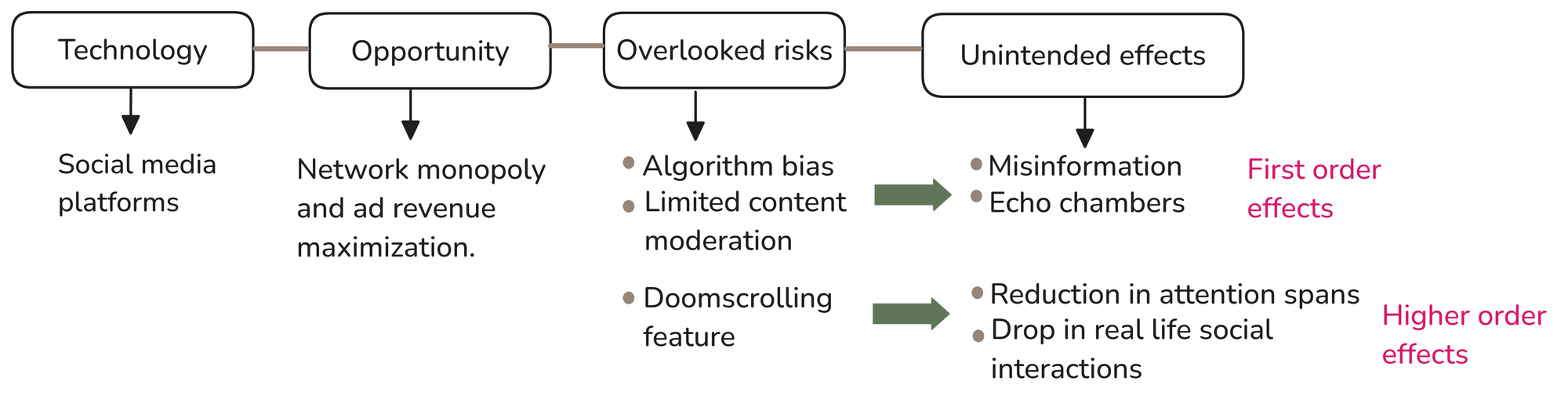

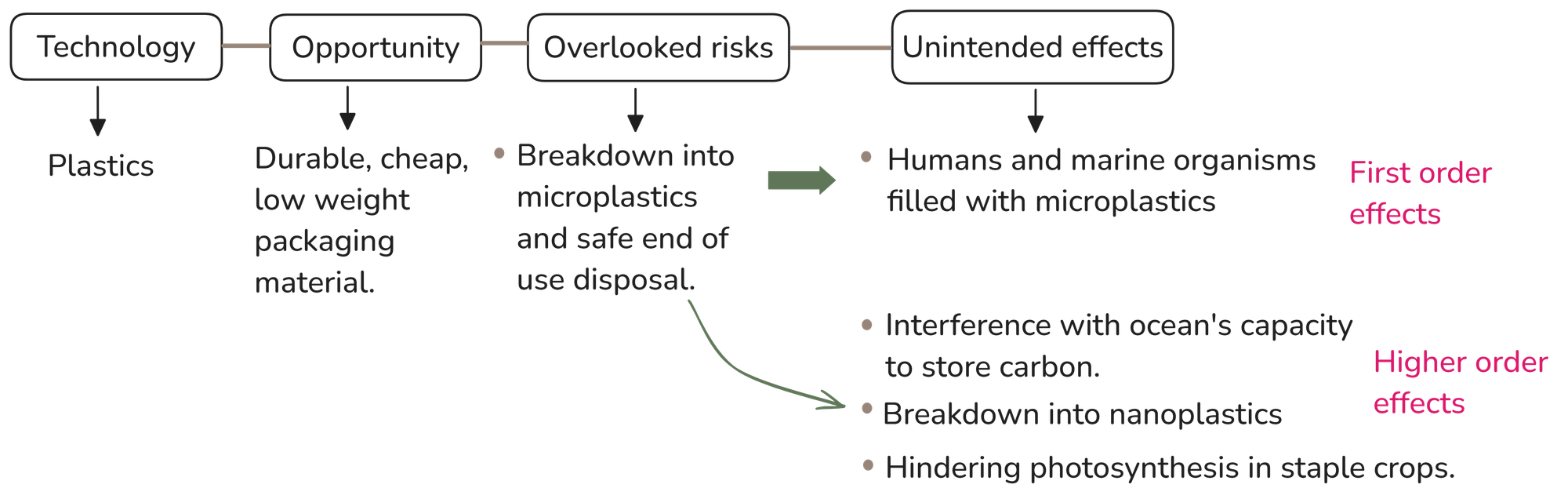

Let’s first identify the higher-order effects linked to current socio-environmental issues, and then examine their characteristics and how they can be mitigated. To do this, we will use a simple template: technology → opportunity → overlooked risks → unintended effects, like the one illustrated below.

In the case of social media platforms, the creators focused on rapid user growth, leveraging network effects and building advertising-based business models. Algorithms and interface design kept users engaged, and society enjoyed the initial benefits. But soon, first-order effects emerged: the spread of misinformation and the creation of echo chambers. Over time, the higher-order effects followed, shrinking attention spans and declining real-world social interaction. Today, it is increasingly debatable whether the benefits of social media outweigh the harms.

We have the advantage of hindsight when assessing social media’s higher-order effects. But for many environmental issues, the long-term consequences have not yet surfaced or are only beginning to appear. This makes it crucial to anticipate, assess, and mitigate them early. In the following sections, we will examine the impacts arising from the adoption of private vehicles and plastics.

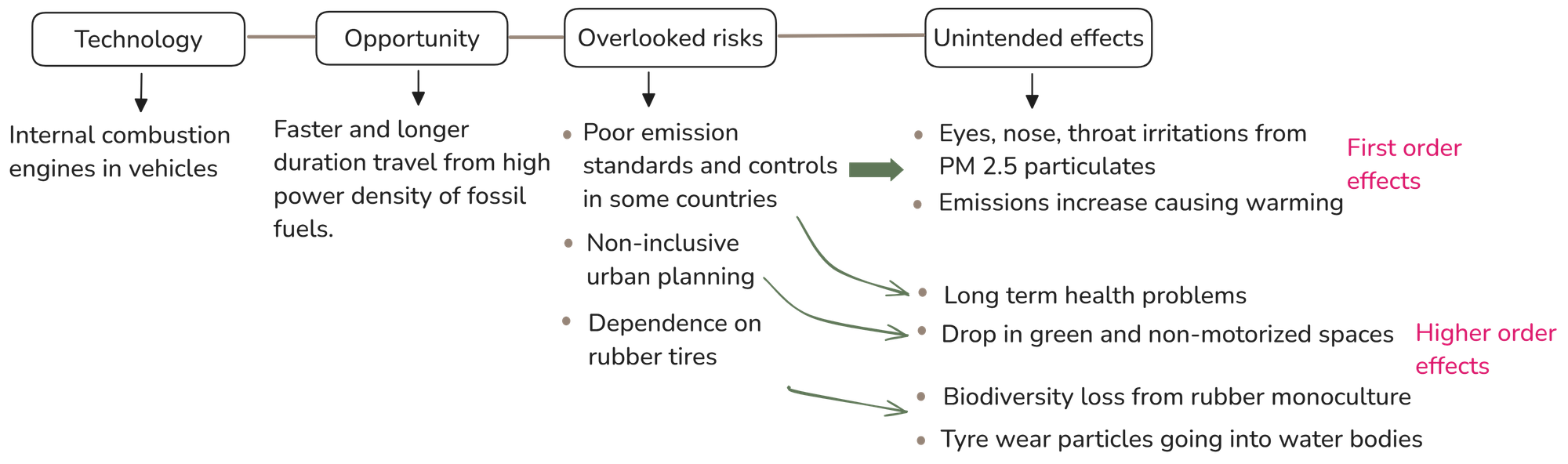

Private vehicles

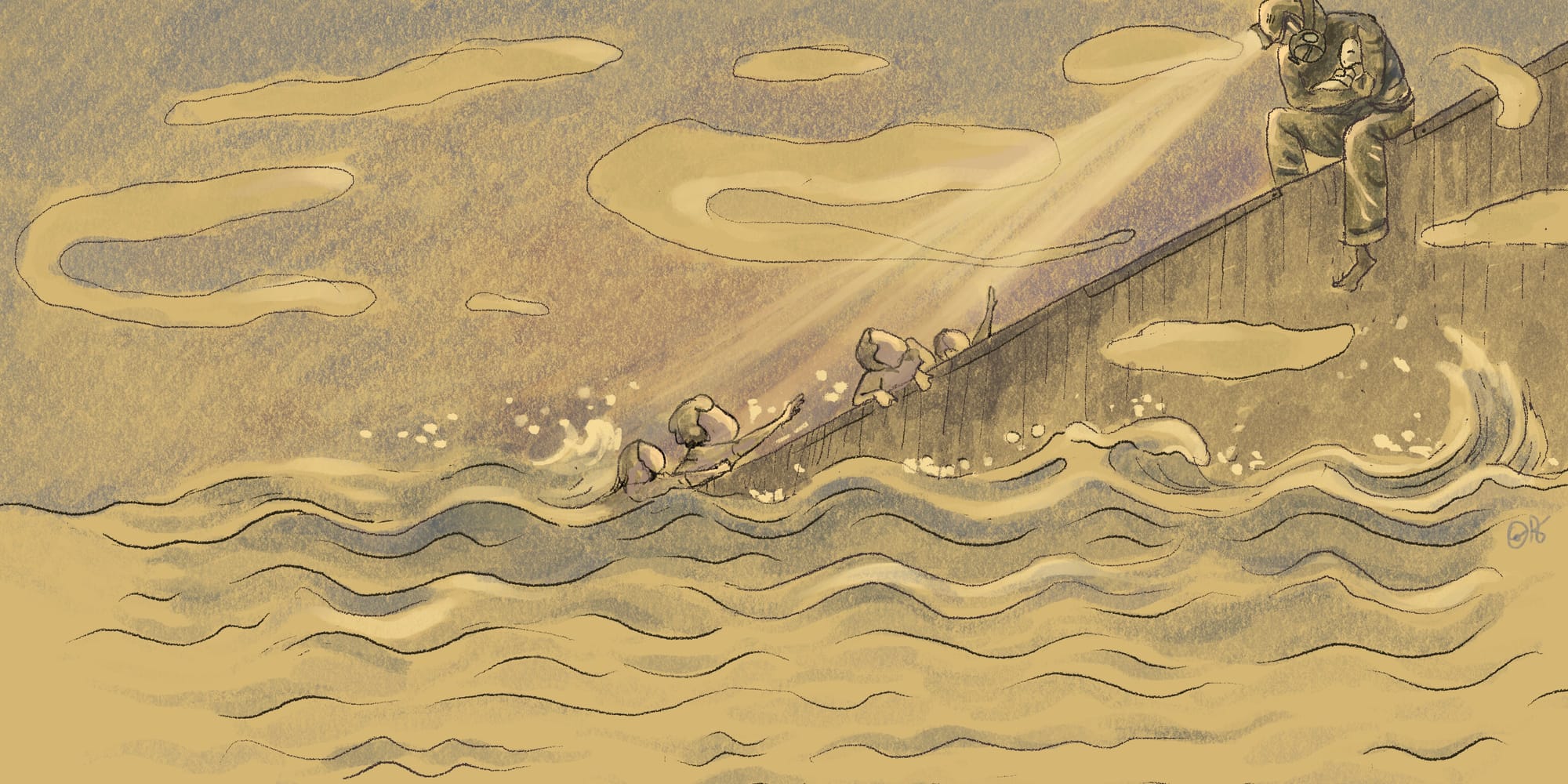

The invention of internal combustion engines (the technology) brought clear benefits: faster travel and longer distances made possible by the high power density of fossil fuels. However, we overlooked two major risks—poor emission standards in many developing countries and our dependence on rubber tyres. The first risk led to PM2.5 levels far above safety limits, causing immediate issues such as eye, nose, and throat irritation (first-order effects). Over time, sustained exposure resulted in severe long-term health problems such as lung cancer and stroke (higher-order effects).

The second risk — reliance on rubber tyres — triggered widespread monoculture rubber cultivation, resulting in biodiversity loss. Tyre wear also contributes micro-particles that wash into water bodies, adding yet another higher-order environmental harm.

In countries like India, stricter enforcement of PM2.5 standards is urgently needed. Instead, PM10 is often prioritised, creating a misleading impression that air pollution is under control.

A clear example of combined higher-order effects can be seen in Bengaluru, India, where widespread car adoption and rapid, unplanned urban growth have squeezed out green spaces and reduced road space for pedestrians and cyclists. Despite the city’s economic boom as the “Silicon Valley of India,” residents now experience a declining quality of urban life. Severe congestion has made Bengaluru’s traffic infamous, prompting local authorities to expand public transport, especially the metro.

However, expanding metro coverage may have an unintended consequence: it could make the city even more attractive to migrants from other states, potentially worsening congestion. A more balanced approach would be to strengthen development in Karnataka’s tier-B cities, making them attractive alternatives and helping ease Bengaluru’s growing influx.

Beyond urban congestion, vehicle dependence has also driven environmental pressures elsewhere. Beyond urban congestion, vehicle dependence has also driven environmental pressures elsewhere. Monoculture rubber cultivation, fuelled by the global demand for tyres, has led to the conversion of primary forests into rubber plantations and significant biodiversity loss. One potential way to reduce reliance on rubber is through tyres made from a special shape-memory alloy called Nitinol. These innovative tyres require minimal maintenance and use less than half the rubber of conventional tyres. However, they are not yet commercially ready.

Tyre wear is still not widely recognised as a problem globally, except in the EU, which has begun introducing tyre-wear limits in its vehicle standards. A British company called The Tyre Collective is leading efforts to address this issue through an electrostatic collector that attaches to a vehicle’s rear mud flap. As the vehicle moves, the device captures the tiny rubber particles shed from the tyres. The collected material can then be recycled into truck-tyre retreads or upcycled into products like shoe soles.

Plastics

Over the past two decades, plastics have become indispensable for shopping bags and packaging, but their disposal has created vast amounts of microplastics. These particles now appear everywhere and have wide-ranging impacts on both humans and marine life. They also interfere with the ocean's ability to sequester carbon. Even worse, they are breaking down further into nanoplastics whose effects will only be known in few more decades.

Microplastics have also started to hinder the photosynthesis of staple crops by damaging soils, blocking water and nutrient channels, and releasing toxic chemicals. Over time, this could contribute to widespread food insecurity.

The higher-order effects of plastics strongly reinforce the need to apply the precautionary principle to all industrial technologies, especially industrial chemicals. The precautionary principle states that when there is uncertainty and a risk of significant or irreversible harm, it is wise to take preventive action before deploying a technology.

Regulators must enforce this principle early, requiring technology creators to anticipate and minimize potential harms. They must also examine how a new technology interacts with other technologies or existing urban systems, and whether these interactions amplify risks or create new ones. This is particularly relevant today, as we see rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI). Its environmental impacts should be assessed through the lens of the precautionary principle to avoid future higher-order effects (more on this in an upcoming article).

Fooled by Incidence rates

Another challenge in recognising higher-order effects lies in the metrics we rely on. Incidence rate — the number of new cases of a disease or event within a population over a given time — can be misleading. It often dulls our perception of emerging risks.

To understand the true severity of a problem, we must also pay close attention to the rate of increase or transmission rate, not just the raw number of cases.

Take cancer cases in India, for example. The country records at least 1.4 million new cancer cases each year, according to the Indian Council of Medical Research’s (ICMR) National Cancer Registry Programme. On its own, this incidence rate appears small relative to India’s population of 1.46 billion. But between 2012 and 2022, cancer incidence rose by nearly 36%, reaching 1.36 million cases in 2022, a trend that is both significant and alarming.

A similar pattern was seen during Covid-19, when many places underestimated the severity of the pandemic by focusing on absolute case numbers instead of the rapid rise in transmission. This oversight contributed to widespread strain on public-health systems.

Incidence rate is a first-order metric, while the rate of increase or transmission rate can be considered a second-order metric. But what about third-order metrics? These require a deeper, more systemic understanding of an issue. Developing that understanding is essential, because third- and fourth-order metrics are far more predictive of emerging higher-order negative effects. This makes it urgent to investigate higher-order metrics for risks such as microplastics, PM2.5 pollution, tyre wear, and pesticide residues in food. Both higher-order metrics and higher-order effects often behave non-linearly, creating a false sense of security during early phases when risks are quietly escalating.

Ultimately, the question is whether we have enough time and enough focus to study these higher-order effects of our industrial technologies before they trigger cascading impacts on our lives.

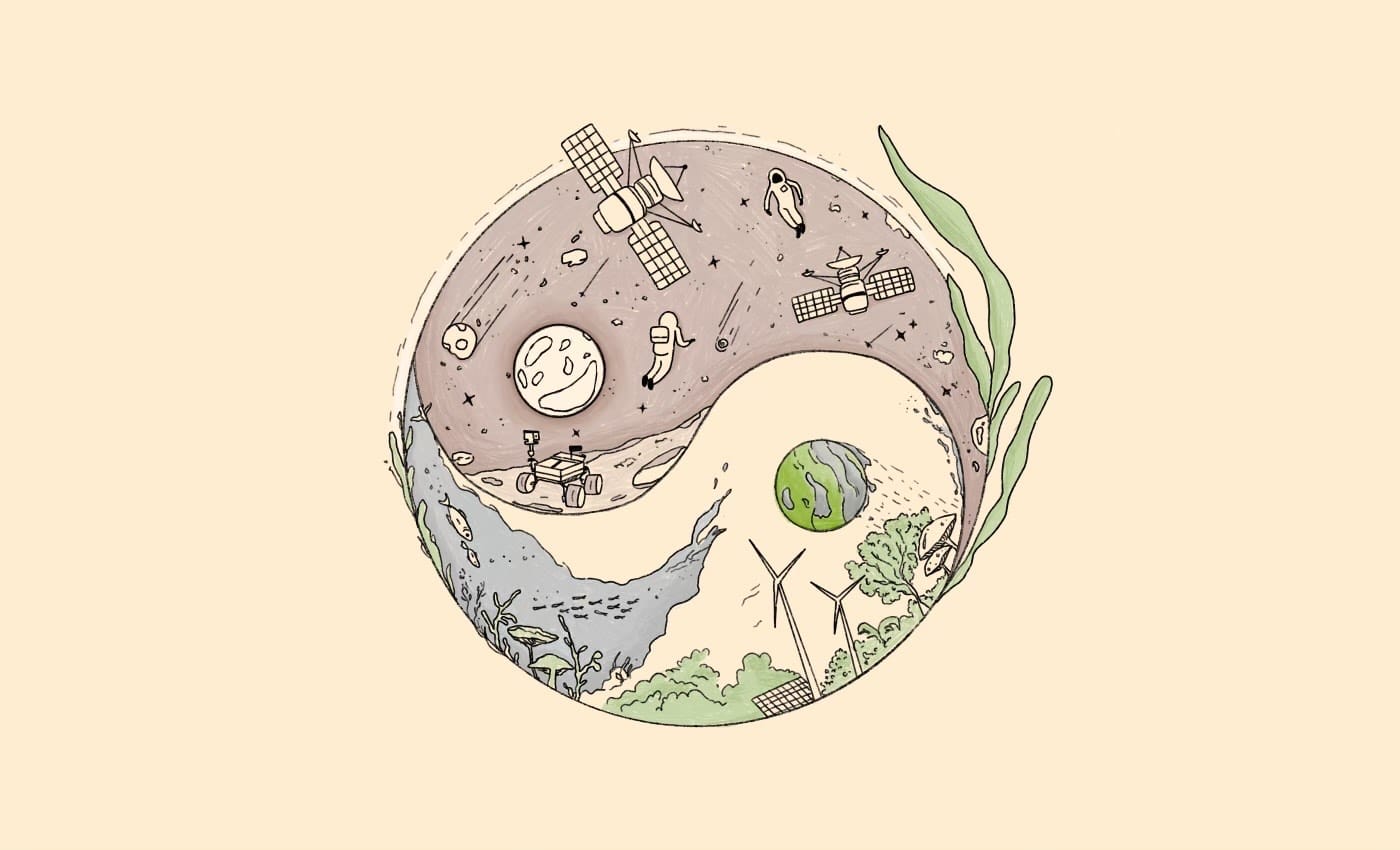

Conclusion

The template used in the three examples above suggests a linear process, but in reality, we are caught in a spiral. To address the higher-order effects of one technology, we often introduce yet another, creating a cycle where new fixes generate new problems. This spiral reflects our deep faith in technology as the solution to every challenge. When that faith goes unquestioned, it can look like progress. But when we examine it critically, we see the risk of spiralling further, driven by our desire to reshape nature to our will, and ultimately burdened by the consequences of our own creations.

We would really appreciate your monetary support if you enjoyed reading this post and found it insightful.

PS: Thanks to Ronojoy for proofreading the article.

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0