How AI consumes energy and why India is a special case

Nature of Energy and water demands from AI deployment in India.

Introduction

When you ask ChatGPT to summarize a document, Nano Banana to generate an image, or GitHub Copilot to suggest a line of code, the response arrives on your screen in seconds. The interface is clean, responsive, and reassuring. Nothing in the user experience indicates where the work happened, what machinery was involved, or what resources were consumed to make that interaction possible.

When you hit enter on your keyboard, a data center received your request. The ‘work’ of answering your response involved processors executing billions of floating-point operations, drawing electricity from a regional grid. The seamless output on your screen was the result of electrical energy converted into compute, and then into waste heat that evaporative cooling systems had to remove.

This is not new information, exactly. We know, in principle, that digital infrastructure runs on electricity. Yet the physical demands of Artificial Intelligence (AI) remain strangely abstract in public discourse. We speak about AI as though it operates in a realm of pure logic - models, parameters, tokens. The language is mathematical, and tech centric. What gets lost in translation is the mundane, physical fact: AI is a process of moving electrons through silicon, and every electron moved generates heat that must be dissipated. The industry calls this ‘compute’.

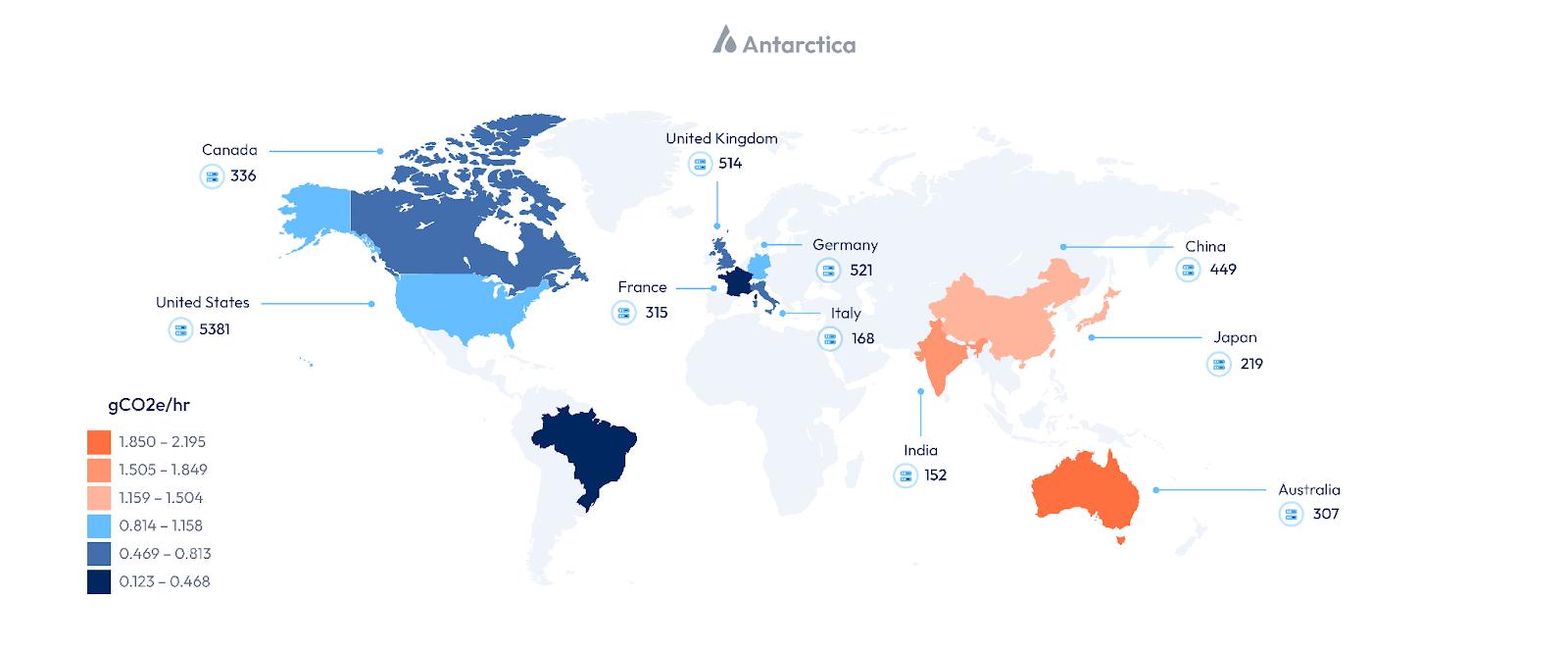

The virtual phenomenon of AI is a physical one. It draws power from regional grids, operates around the clock, and in many regions extracts copious volumes of freshwater from already water-stressed aquifers. Geographical distribution of AI resources thus becomes an important factor to consider.

However, our entire focus of AI’s energy demands has been on the Global North, where capital, research, and model development are concentrated. Far less attention has been paid to the South Asian context, where the physical infrastructure required to operate AI at scale is increasingly being deployed.

This raises a deeper question: whether the current geography of AI infrastructure risks reproducing a familiar pattern, in which the economic and productivity gains of technology are largely captured by enterprises and consumers in the Global North, while a disproportionate share of the environmental and resource externalities is borne by regions in the Global South, like India.

This essay examines questions like these across three sections. First, it explains AI's energy physics. Second, it explores India's AI landscape and differences from the Global North in terms of AI. Third, it documents consequences already visible on the ground: communities, water access, neighborhoods experiencing worsened air quality, populations absorbing negative externalities from development they did not choose and may not benefit from.

How the energy physics of AI is different from other digital technologies

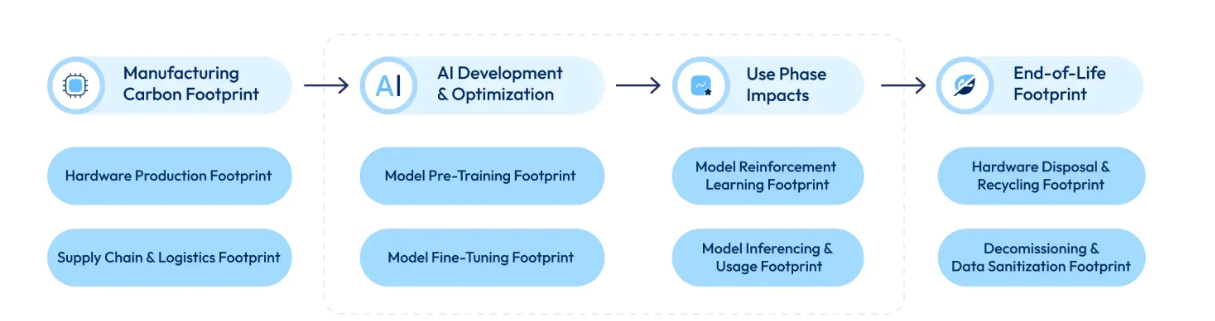

Let’s start with the first question. AI is often discussed as though it were primarily a software phenomenon: models, parameters, architectures, and benchmarks. In practice, AI’s use-phase is better understood as an industrial process with two distinct operational phases, each with very different energy characteristics and geographic implications.

The first phase is training. This is the stage at which a model learns. Engineers expose the system to massive datasets: text, images, audio, code, while specialised processors called graphics processing units (GPUs) iteratively adjust billions of internal parameters. Training typically runs for weeks or months, requiring thousands of GPUs operating in parallel at high utilisation. Electricity consumption during this phase reaches industrial scale, comparable to that of energy-intensive manufacturing facilities.

Because training is both capital-intensive and technically complex, it remains concentrated in a relatively small number of locations. These are hyperscale data centers in regions such as Iowa, Virginia, Oregon, or parts of Scandinavia, where access to large tracts of land, reliable power, advanced cooling infrastructure, and favourable regulatory regimes converge. This concentration explains why training has dominated public discussion of AI’s environmental footprint: it is visible, episodic, and comparatively easy to measure.

Table 1: AI Training Environmental Impact

| Metric | GPT-3 (Official 2020) | GPT-5 (Estimated 2025/2026) | The Scale Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 1,287 MWh | ~3,500 – 4,000 MWh | ~3x increase |

| Carbon (CO2e) | ~550 metric tons | ~1,500 – 2,000 metric tons | ~3-4x increase |

| Water | 700 kL | ~2,000+ kL | ~3x increase |

Source: (Making AI Less Thirsty, 2025), (Juma, 2024), (Extreme Networks,2024), Author’s calculations (see notes at the end).

These numbers are large, but they represent a one-time or episodic cost. Once training is complete, the model exists. What follows is the second phase: inference.

Inference is what happens every time a trained model is used. Each time a user asks a question, generates an image, receives a recommendation, or triggers a real-time translation, the model processes that request and returns an output. Individually, inference operations are relatively lightweight. A single query to GPT-4 used to consume roughly 0.42 watt-hours (Epoch AI, 2025).

The significance of inference lies not in the energy cost of a single request, but in its frequency and persistence. Inference does not occur once; it occurs continuously, at massive scale, for as long as the service remains operational.

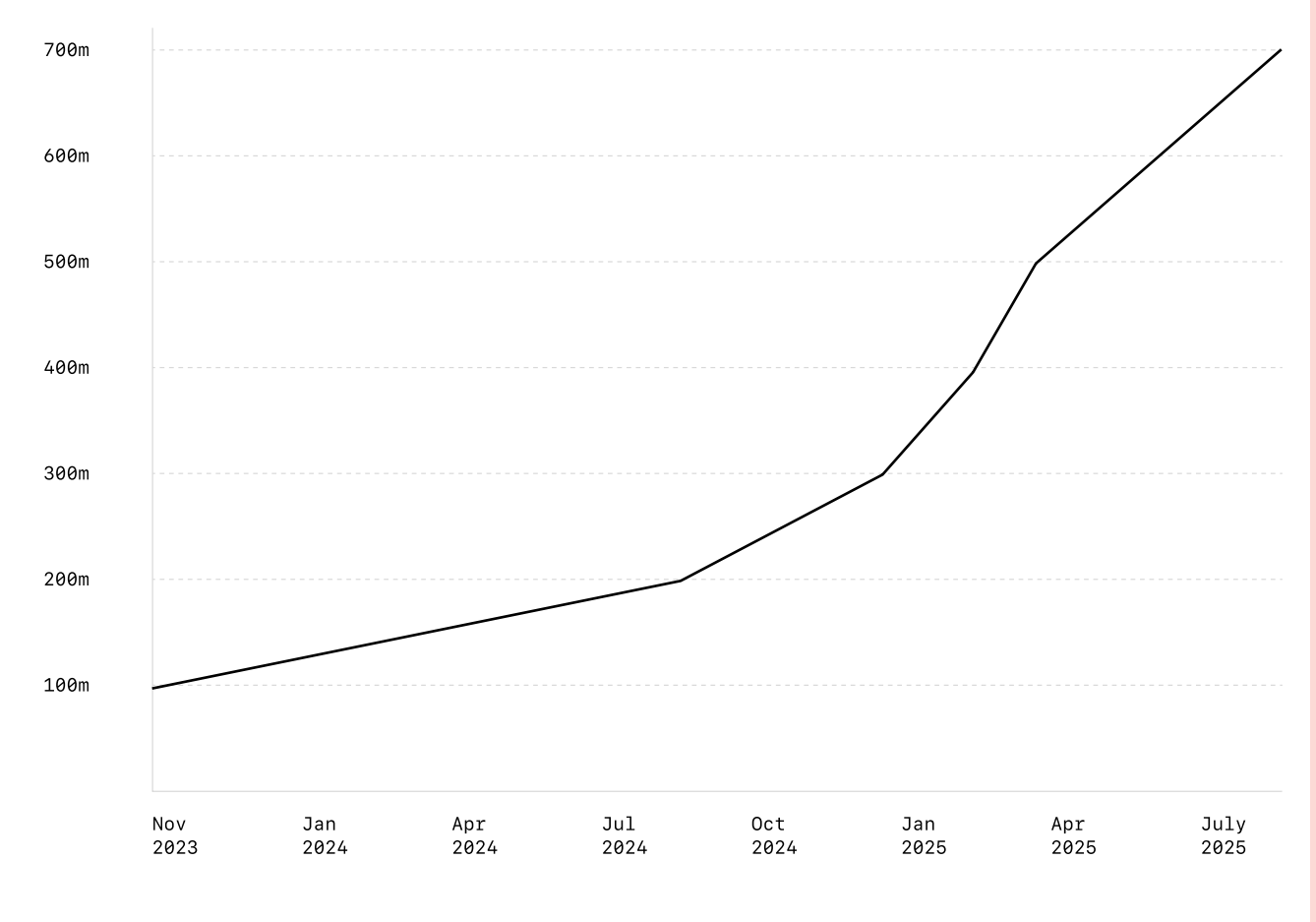

As of late 2025, ChatGPT has surpassed 800 million weekly active users, and was processing over 6 billion tokens per minute on the API (Tech Crunch, 2025).

A frontier AI model does not sit idle overnight or rest on weekends, they run at sustained capacity, processing requests as they arrive. As a result, inference now accounts for the majority of energy consumed over a frontier model’s lifecycle. Major AI operators such as Google and Meta estimate that 60–70 percent of total AI energy use during usage occurs during inference, not training (Alex de Vries, 2023).

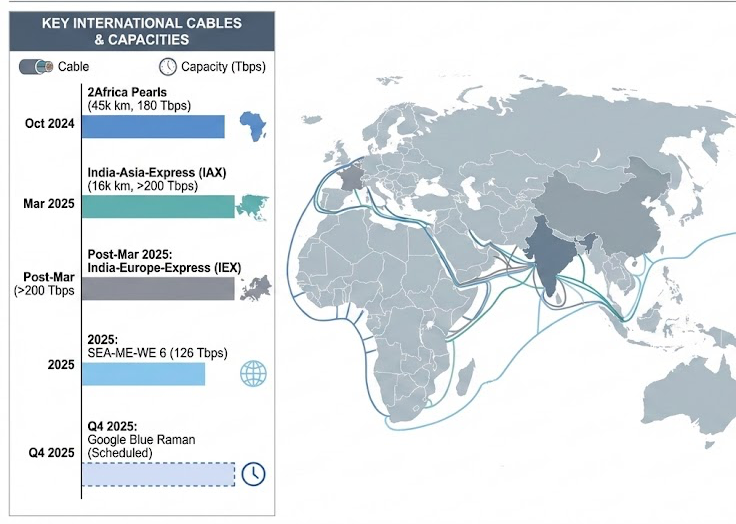

Crucially, inference does not remain geographically concentrated. It follows people.

Latency sensitivity makes this unavoidable. When a user interacts with an AI, their request must travel to a data center, be processed, and return within milliseconds. Routing traffic across continents introduces delay, increases network costs, and degrades user experience. At scale, even small increases in latency reduce adoption and raise operating costs.

And as AI becomes embedded in everyday digital services: search, payments, education, healthcare, customer support, the economic logic converges on a single outcome: deploy inference infrastructure close to population centers. Over time, this redistributes AI’s energy footprint away from a handful of training hubs and toward regions with large user bases.

This distinction between training and inference matters because it alters the geography of impact. Training concentrates energy use where models are built. Inference concentrates energy use where models are used. As AI adoption reaches population scale, energy demand becomes a function of geography and demographics.

It is this shift: from episodic, centralized energy consumption to continuous, distributed base load, that makes countries like India central to the future energy and environmental footprint of AI, even when many of the models themselves are trained elsewhere.

The economic, regulatory and geopolitical ecosystem fuelling India’s AI growth

The relocation of AI inference infrastructure toward India is the outcome of several reinforcing forces: demographic, economic, regulatory, and geopolitical, that together make India one of the most consequential locations for AI deployment globally.

- At the foundation lies the scale of demand.

India has over 800 million internet users, generating a disproportionate share of global digital interactions (MeitY, Government of India, 2022). Despite accounting for ~20% of global data demand, the country hosts only ~3% of operational data center capacity (Deloitte, 2025), creating a strong economic incentive to localize compute infrastructure.

- This demand is met by a large and rapidly expanding AI-capable workforce.

India has emerged as one of the world’s largest software development hubs, ranking second globally in contributions to AI projects on GitHub, with a 14× increase in AI-skilled workers between 2016 and 2023. The Stanford AI Index places India among the top four countries globally in AI skills, capabilities, and policy readiness, accelerating domestic AI development and usage (MeitY, Government of India, 2025)

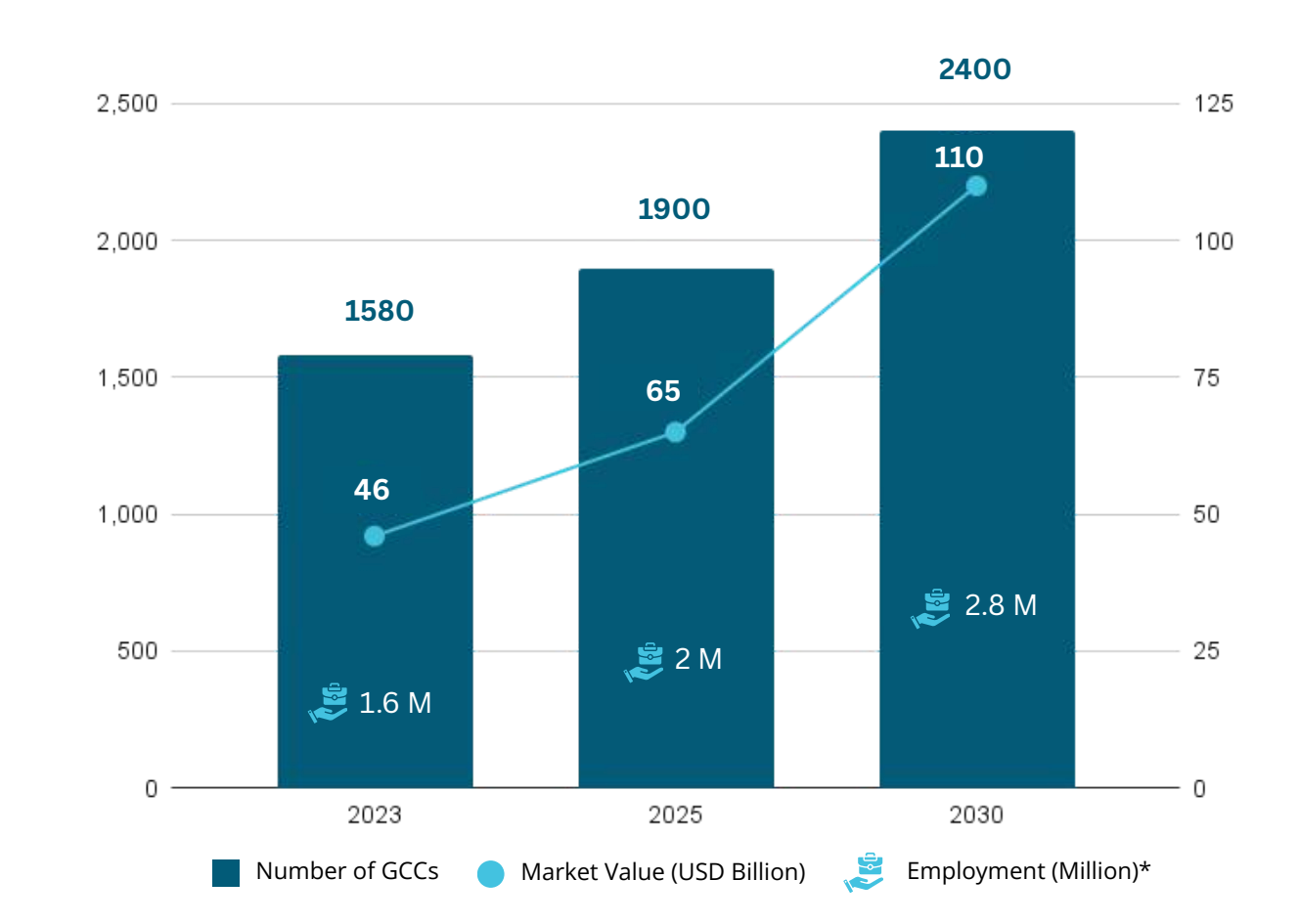

- Global Capability Centers (GCCs) operating continuous AI workloads

- The number of GCCs in India is estimated to grow to 2400 by 2030 as shown in the figure below (TeamLease Regtech, 2025). These centers support real-time, always-on applications for global markets (ET GCC World, 2026).

- Roughly 92% of GCC employees are working on AI tools, the highest globally, with over 70% of centers actively investing in Gen AI, translating directly into a stable, 24×7 base load of inference traffic anchored within Indian data centers (Zinnov and Prohance, 2025).

The economic case for locating AI infrastructure in India is compelling. From an OpEx perspective, India is unusually competitive.

In 2025, operating a data centre in India averaged just US$7 per watt, significantly cheaper than the US (US$10/W) and UK (US$11/W), and nearly matching China (US$6/W) (Takshashila, 2025). This OpEx runs 15-25% below those in developed markets, driven by lower labor costs, and electricity tariffs that, in certain regions with state-level incentives, can be 40-60% lower than in the US or Europe. Land costs remain substantially lower in emerging hubs with exceptions like Mumbai (Kushman and Wakefield, 2022).

These cost differentials matter at scale: inference margins are thin, and profitability depends on minimizing both CapEx and long-term OpEx.

Under the India AI mission (India AI, 2026), data centers have been granted infrastructure status, enabling access to lower-cost financing and tax benefits typically reserved for roads, ports, and power plants. For instance, the government permits 100% foreign direct investment in the semiconductor sector (Dun and Bradstreet).

Data localization from regulatory pressures is another major driver of this demand. Taken together, state-level (Nasscom, 2025).and sectoral regulations, most notably RBI’s payment data localization mandates, SEBI’s stringent cloud and cyber-resilience frameworks (SEBI, 2023), (CSCRF, 2024) and the DPDP Act’s (DDPA Act, 2023) power to restrict cross-border transfers, create strong regulatory gravity toward data localization, making domestic data centers the path of least resistance for multinational firms operating in India.

Geopolitical factors compound these structural drivers. The ongoing US-China technological decoupling has made India a strategic alternative for Western companies seeking to reduce dependence on Chinese supply chains and infrastructure. China's AI investment has contracted sharply, dropping to $9.3 billion in 2024 compared to $109 billion in the United States, largely due to tightening government oversight (Stanford AI Index Report, 2025).

India has positioned itself as a democratic, trustworthy partner without the regulatory uncertainty and political risk associated with Chinese operations. India occupies a deliberate middle position between what scholars have termed American "techno-liberalism" and Chinese ‘techno-authoritarianism,’ making it attractive to firms seeking stable, long-term operations outside the bipolar tech rivalry.

In response to these converging forces, AI providers have moved systematically to anchor inference infrastructure inside India through high-profile partnerships and direct investments.

Table 2: AI providers and Indian Telecom partnerships

| Company | Partnership / Investment | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Partnership with Reliance Jio | Access to 505 million telecom users of India's Reliance Jio | |

| Perplexity | Distribution agreement with Airtel | Access to ~360 million Airtel customers across mobile, broadband, and DTH. |

| OpenAI | Region-specific pricing + ChatGPT Go launch | Market-wide, at population scale |

| Microsoft | Azure cloud and AI infrastructure expansion | Largest investment in Asia: US$17.5 billion over four years (CY 2026 to 2029) - at population scale |

| Amazon Web Services | Hyperscale and edge data center investments | Multi-$B commitments (up to ~$35 B by 2030), at population scale |

Domestic conglomerates have responded with equivalent commitments. Reliance Industries (RIL, 2025), Adani Group (Adani, 2025), and Tata Group (Tata, 2025) have each announced multi-billion-dollar AI infrastructure plans, creating competitive pressure that reinforces the investment wave.

This dynamic, where early movers create network effects that attract additional capital, has produced a self-reinforcing cycle: more infrastructure enables greater adoption, which drives higher demand, which justifies further infrastructure expansion. These commitments represent operational decisions with physical consequences: if hundreds of millions of people in India will use AI services daily, those services must run on servers located in India, drawing power from Indian grids, cooled by Indian water.

Beyond market incentives and regulatory pull, India’s accelerating investment in AI infrastructure is driven by a deeper strategic objective: domestic AI sovereignty.

India’s domestic AI sovereignty

The Indian government has made AI development a national priority under the vision of ‘Making AI in India and Making AI Work for India’. AI is projected to contribute $1.7 trillion to India's GDP by 2035 (IBEF, 2025). Capturing even a fraction of this value requires more than access to foreign models or cloud services; it requires domestic capacity to train, deploy, and govern AI systems aligned with local priorities.

The IndiaAI Mission, launched in 2014 operationalizes this through deploying 38,000 GPUs to democratize compute access; developing foundation models; creating AIKosh, a national repository, training AI specialists; providing startup support and incubation; and establishing frameworks for responsible AI governance (IndiaAI, 2025).

What distinguishes these efforts from earlier waves of digital policy is their dependence on sustained, local compute. Sovereignty in AI does not arise from ownership of code alone. It requires the ability to run models continuously, adapt them to local conditions, retrain them as data evolves, and serve outputs with low latency and high reliability. In practice, this means operating substantial inference infrastructure within national borders.

Table 3: Sovereign Indian Foundational AI Models in development

| Initiative | Lead Org | Model Type | Primary Focus | Strategic Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BharatGen | GOI (IIT Bombay–led) | Multilingual multimodal models (up to ~1T parameters) | General-purpose sovereign AI, public digital infrastructure | Strong open-source emphasis; cornerstone of India's sovereign AI stack |

| Sarvam-1 | Sarvam AI | 2B-parameter LLM | General language understanding & generation | Open-source; optimized for Indian linguistic context |

| Hanooman AI | Hanooman AI | Large multilingual LLM | Conversational & enterprise AI | Focus on scale across diverse Indian languages |

| Chitralekha | IndiaAI ecosystem | Specialized video AI | Video transcreation & localization | Targets media accessibility and regional content |

| Bhashini Platform | MeitY | Real-time translation infrastructure | Speech/text translation for public services | Public digital good; hard for foreign models to replicate |

| Krutrim | Ola Krutrim | Large proprietary LLM | General-purpose & consumer AI | Commercial sovereign LLM stack |

| Avataar.ai Models | Avataar.ai | Domain models (up to ~70B parameters) | Agriculture, healthcare, governance | Domain-specific depth over generality |

| Fractal Reasoning Model | Fractal | Large reasoning model | STEM & medical reasoning | Enterprise and research-oriented |

| Orion (Agentic AI) | Tech Mahindra (Makers Lab) | 8B-parameter Indic LLM + agents | Enterprise automation & agents | Industry-grade, applied AI |

| Genloop Models | Genloop | Small, efficient language models | Cost-efficient language AI | Emphasis on efficiency and deployment |

| Shodh AI | Shodh AI | Research-focused AI models | Material discovery & R&D | Scientific and industrial innovation |

| NeuroDX | NeuroDX (Intellihealth) | Specialized signal-processing AI | EEG analysis & healthcare | High-value medical specialization |

These efforts respond to India's linguistic diversity: 22 official languages and 780 living languages, which creates unique technical requirements poorly served by English-centric models developed abroad. (Government of India, 2025)

India’s domestic AI innovation is underpinned by a uniquely mature Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) that has achieved population-scale adoption across sectors. Near-universal financial inclusion, enabled by the JAM trinity (Jan-dhan bank accounts, Aadhar, and mobile connectivity) has brought over 520 million people, predominantly from rural and semi-urban areas, into the formal economy, creating vast, data-rich systems that now demand AI for fraud detection, credit assessment, and inclusive financial services (BCG, 2023). This same DPI foundation will support large-scale AI deployment across education (personalized learning for millions of students), healthcare (telemedicine and diagnostics in underserved regions), agriculture (crop monitoring, yield prediction, and market access for a workforce exceeding 500 million), and government (AI-driven digital governance and citizen services). Together, these sectors create real-world, high-volume use cases that both require and accelerate indigenous, scalable AI solutions.

Yet all of this: the policy incentives, the connectivity infrastructure, the market opportunity, and the geopolitical positioning ultimately translates into a single physical requirement: continuous, reliable energy and adequate cooling water. This is where the energy implications become distinct from those in the Global North.

Energy sovereignty is a prerequisite for India’s AI sovereignty

India’s ambition to build domestic AI capability ultimately resolves into a question of energy.

India's single data center IT load capacity, a measure of how much computing equipment facilities can actively support, is expected to more than triple to 4.7 GW by 2030, from 1.3 GW in April 2025, driven by rising cloud adoption and AI workloads (Mordor Intelligence, 2025). For context, this projected addition of roughly 35 GW of IT load capacity is equivalent to adding continuous electrical demand comparable to a mid-sized Indian state.

India’s energy ambitions are growing, but its grid is operating close to capacity. National electricity demand has been rising at roughly 6–7% annually in recent years, driven by income growth, air conditioning adoption, vehicle electrification, industrial expansion, and urbanization. However, 2025 growth did moderate to about 4% after cooler summer temperatures in the first half of the year reduced consumption and shifted peak load to September (IEA, 2025).

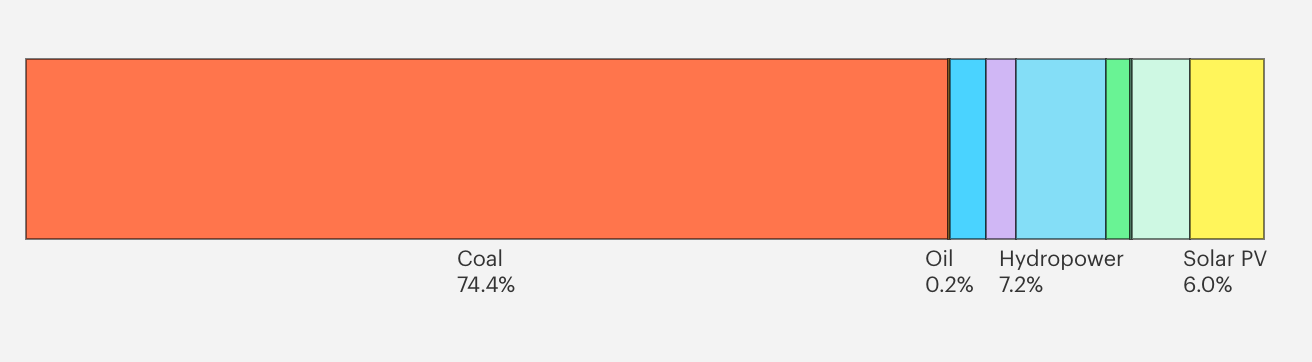

The fuel mix further complicates this picture. India installed a record 44.5 GW of renewable capacity in the first eleven months of 2025, far exceeding earlier annual records, with solar accounting for the bulk of additions (Ministry of New and Renewable Energy, 2025). Nevertheless, coal still supplies approximately 70–72% of total electricity generation, while renewables contribute around 17–18% (IEA, 2025).

More critically, coal and natural gas dominate marginal dispatch: they are the power plants activated when demand rises or when renewable output falls due to intermittency.

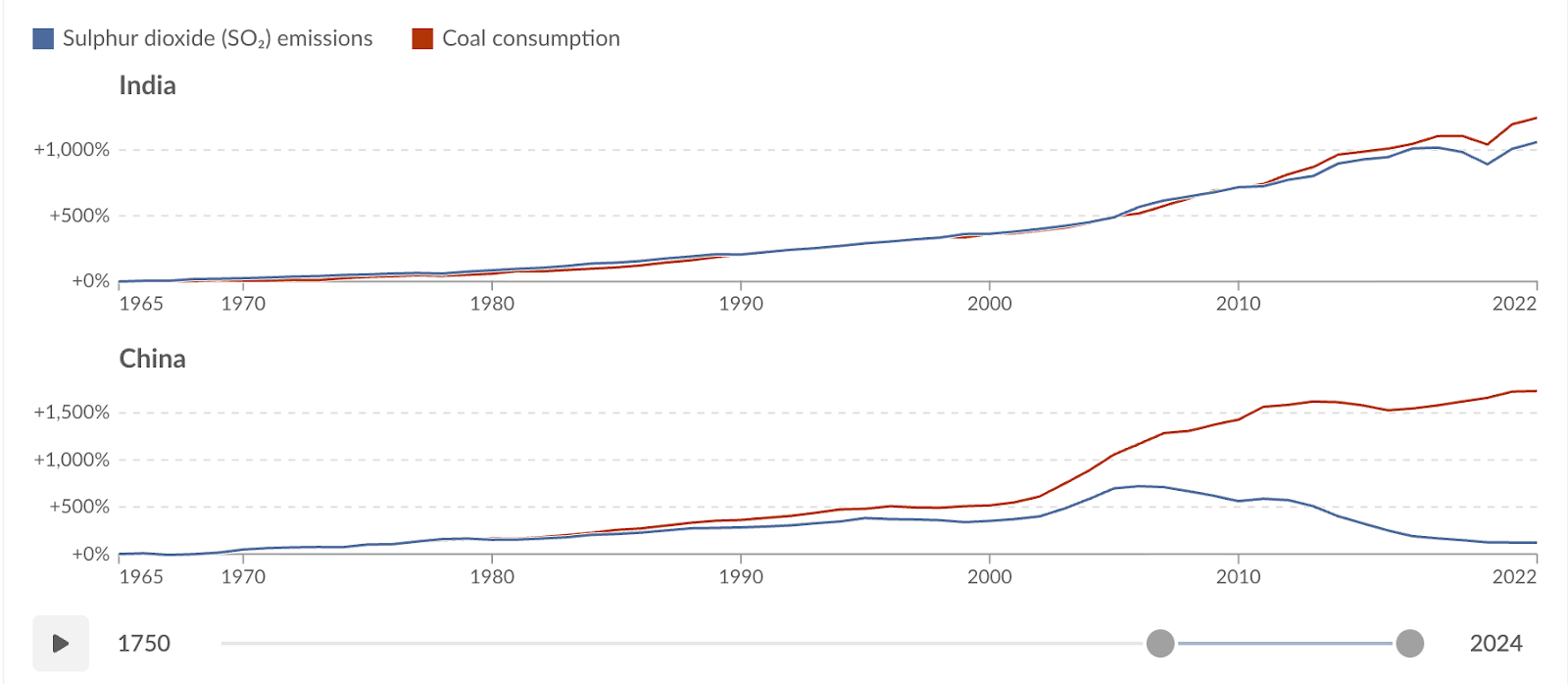

This reliance on coal has qualitatively different consequences in India than in some other large coal-dependent countries. China, for example, still generates roughly 60 percent of its electricity from coal, a profile not different from India’s. However, China has implemented flue-gas desulphurisation (FGD) units and other end-of-pipe pollution controls across the vast majority of its coal fleet over the past decade. As a result, sulphur dioxide emissions in China have declined sharply even as coal consumption continued to rise.

India’s coal fleet has followed a different trajectory. As illustrated in the figure below, sulphur dioxide emissions in India closely track coal consumption, reflecting the slow and uneven deployment of FGD systems and weaker enforcement of emission standards. In practice, this means that additional coal-based electricity in India translates into more detrimental air quality impact for local communities.

The implication is that AI-driven electricity demand in India does not merely increase carbon emissions; it intensifies local environmental and health externalities in ways that are far more immediate and politically salient.

When a new data center in Visakhapatnam begins drawing tens or hundreds of megawatts continuously, the incremental electricity required to meet that load is overwhelmingly likely to come from fossil‑fueled sources, not renewables.

This dynamic will persist until India either deploys large-scale battery energy storage and pumped storage hydropower sufficient to make renewables dispatchable or retires coal capacity faster than new base-load demand absorbs it. In the near to medium term, neither condition holds. AI-driven load growth therefore risks hard-wiring higher fossil utilization into the grid, even as renewable capacity expands in parallel.

In response to these constraints, some technology leaders in the Global North have begun advocating for nuclear power as a solution for AI’s energy demands, citing its high reliability and low carbon intensity. Meta is investing heavily in nuclear energy to power its AI data centers, signing deals for over 6.6 gigawatts of capacity with partners like Vistra, TerraPower, and Oklo (Meta, 2026).

These initiatives, starting in 2026, aim to secure clean, 24/7 "baseload" power for AI, involving both upgraded existing plants and new, small-scale reactors. While nuclear power offers high spatial power density and stable baseload generation, it is not a near-term solution for India.

New nuclear projects involve long development timelines, complex regulatory processes, high capital costs, and political constraints. Even under optimistic assumptions, nuclear capacity cannot be deployed at the speed or scale required to support the rapid expansion of AI inference infrastructure over the next decade.

This leaves solar power as the most frequently proposed alternative. However, solar introduces a structural constraint that is often underappreciated in discussions about AI energy: spatial power density (SPD). SPD measures how much usable power can be generated per unit of land area. Fossil fuel plants and nuclear facilities exhibit very high SPD, producing large amounts of power from compact sites. Solar, by contrast, has a low SPD, requiring extensive land area to generate equivalent continuous power.

Recent analysis illustrates this challenge in the United States, where meeting incremental electricity demand from data centers with solar would require vast new land allocations, even in a country with abundant open space. The constraint is significantly more acute in India. India’s population density is more than three times that of the United States, and land is already under intense competition from agriculture, housing, industry, and infrastructure. Unlike the US, India does not possess large reserves of low-conflict, contiguous land suitable for utility-scale solar deployment near major load centers.

Moreover, AI inference workloads require continuous, 24×7 power, while solar generation is inherently intermittent. Without massive investments in storage, solar capacity alone cannot supply the stable baseload demanded by large-scale data centers. In practice, this means that even if new solar installations are built to nominally “offset” AI-driven electricity demand, fossil generation remains necessary to provide reliability during nighttime hours, seasonal variability, and peak load conditions.

The spatial power density constraint thus represents a fundamental counterpoint to the argument that AI’s energy demands can be solved simply by deploying more solar panels. In land-constrained, densely populated regions such as India, the question is not whether solar capacity can grow, but whether we have enough land, can it grow fast enough, close enough to demand centers, and with sufficient storage to support always-on digital infrastructure without deepening reliance on fossil fuels.

Water introduces a parallel constraint. Data centers generate heat continuously, and that heat must be removed to prevent thermal throttling and equipment failure. Most facilities rely on evaporative cooling: water absorbs heat and releases it as vapor.

Industry benchmarks indicate a data center requires approximately 25 million liters of water per megawatt of IT load capacity annually (World Economic Forum, 2024). India's data center sector consumed an estimated 150.30 billion liters in 2025 and is expected to reach 358.66 billion liters by 2030, at a CAGR of greater than 19% during the period (2025-2030) (Mordor Intelligence, 2025).

Many of India's major regional data center hubs: Mumbai, Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad, are located in regions the World Resources Institute classifies as facing "extremely high" baseline water stress, where annual water withdrawals represent more than 80% of available supply (Residents Watch, 2025) with accelerating groundwater depletion.

In Devanahalli, a peri-urban district north of Bangalore where at least eight data centers have received government clearance since 2013, the stage of groundwater extraction, the percentage of water used relative to annual extractable resources stands at 169%, sixty-nine percentage points above the permissible threshold. This is the highest extraction rate in Bengaluru Rural district. Residents report wells that once provided water at 20-30 feet now require drilling to 100 feet or failing entirely, forcing reliance on expensive tanker deliveries. In one documented case, a proposed data center received authorization to withdraw 650 kiloliters daily, more than twenty times the neighboring village's total consumption (Down to Earth, 2025).

Environmental regulation governing data centers and digital infrastructure exists in India but remains insufficiently aligned with the energy and resource demands introduced by large-scale AI workloads. While early efforts to integrate sustainability considerations into digital infrastructure policy are emerging in parts of Europe, these frameworks remain nascent globally and have yet to fully address the continuous, high-intensity compute loads associated with AI training and inference. In India, regulatory oversight covers industrial water withdrawal, air emissions from backup diesel generators, and effluent discharge standards; however, responsibility for enforcement is fragmented across state pollution control boards, municipal authorities, and utility regulators.

The draft National Data Centre Policy (Government of India, 2020) prioritizes investment facilitation and infrastructure expansion and does not mandate the disclosure or monitoring of operational efficiency metrics such as Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE), which are increasingly tracked in jurisdictions such as Singapore, China, and parts of Europe.

In practice, many Indian data centers rely on diesel generator sets not only during grid outages but also during periods of voltage instability and frequency deviations. These generators emit particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and carbon dioxide directly into urban environments that already exceed World Health Organization air quality guidelines, compounding existing public health and environmental pressures.

AI workloads compound these stresses.

Traditional enterprise data center workloads, such as web hosting, email, and transactional databases, typically exhibit variable demand patterns, with traffic peaking during business hours and declining overnight or on weekends. As a result, servers often operate at relatively low average utilization levels (IEA, 2025), historically on the order of 20–30 percent in many enterprise and colocation environments (Google, 2018). During periods of low demand, capacity can be throttled, consolidated, or temporarily powered down, providing a degree of operational and grid-level flexibility.

AI inference workloads exhibit a materially different load profile. While demand may still vary across time zones and use cases, inference systems are characterized by high minimum utilization, latency sensitivity, and limited tolerance for interruption.

A single rack of modern AI accelerators can draw on the order of 60 to 120 kilowatts of continuous power, whereas more standard data centers typically use 5-10 kilowatts per rack (PC Mag, 2024). By comparison, the average Indian household consumes approximately 100 to 150 kilowatt-hours of electricity per month (Data for India, 2024), implying that a single AI rack can impose an instantaneous load comparable to that of dozens of households combined. Unlike residential or conventional enterprise demand, which fluctuates with daily routines, AI inference workloads maintain a high base load with relatively shallow off-peak periods.

As AI capacity scales, through higher concurrency, richer multimodal outputs, and lower latency expectations, this sustained demand translates into a growing continuous base load on electricity grids. Where grids lack sufficient low-carbon, dispatchable capacity, the response is structural rather than discretionary: coal-fired plants operate at higher plant load factors, diesel generator sets are activated to maintain power quality and uptime, and water-intensive cooling systems place additional stress on municipal supply networks and groundwater aquifers.

The resulting environmental burden, spanning Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, ambient air pollution, and local water depletion, falls disproportionately on communities proximate to data center infrastructure, many of whom derive limited direct benefit from the AI services being delivered.

This is a lived reality for many.

In the United States, wholesale electricity costs in areas near data centers have risen 267% over five years. Baltimore residents saw average monthly bills increase by $17 after capacity auctions held by PJM Interconnection, the largest grid operator in North America reached record prices driven partly by projected data center demand. Across seven mid-Atlantic and Midwest states served by PJM, consumers paid $4.3 billion in 2024 alone for local transmission upgrades required to connect data centers to the grid, costs that were socialized across all ratepayers rather than assigned to the facilities themselves. By 2028, analysts project the average household in the PJM region will see energy bills rise by $70 per month, $840 annually, due to data center-driven capacity costs (Bloomberg, 2025).

In South Asia, the collision between AI's requirements for stable, continuous power and the structural limitations of regional grids is already underway. Models may be trained in California or Scandinavia, but the energy cost of operating them billions of times daily is increasingly borne by electricity systems that were not designed for this type of persistent, heavy base load.

The choices that will shape India’s AI future

This tension is sharpened by the fact that India remains a developing economy with competing and unfinished energy priorities. In a capital- and energy-constrained economy, prioritization is unavoidable. Treating AI compute as neutral demand obscures the fact that it competes directly with other development uses of electricity. The question is under what conditions its growth justifies its claim on scarce resources.

Electricity is a development input, required to meet foundational infrastructure needs: affordable housing, industrial growth, transport electrification, agricultural productivity, healthcare delivery, and the achievement of core Sustainable Development Goals. In this context, allocating large increments of scarce, dispatchable power capacity to support AI inference infrastructure raises a legitimate question of opportunity cost.

Every megawatt committed to always-on digital services is a megawatt unavailable, at least in the near term, for other development-critical uses.

The justification for this allocation is often framed in terms of employment generation, digital empowerment, and productivity gains. Yet this rationale depends critically on how AI is deployed within the IT and services sector itself. If AI primarily augments human labor, enabling higher-value work, improved service delivery, and broader participation in the digital economy, the case for prioritizing energy allocation to AI infrastructure is strengthened.

If AI is deployed predominantly as a labor-substituting technology, reducing headcount while increasing compute intensity, the developmental logic becomes far less clear. In that scenario, the energy and environmental costs are borne locally, while employment gains and economic benefits may be limited or even negative for the domestic workforce.

These considerations do not negate the potential value of AI for development. They do, however, complicate the assumption that expanding AI infrastructure is an unqualified public good. In energy-constrained regions, the relevant question is whether its growing claim on electricity, water, and grid capacity aligns with broader development objectives, labor outcomes, and social priorities.

To understand AI's energy consumption, and why India represents a distinct case. requires seeing AI as infrastructure. It is a continuous industrial process: electricity converted to computation, computation generating heat, heat requiring removal through thermal management systems.

Every capability increase is fundamentally a power systems problem, contingent on generation capacity, transmission infrastructure, fuel availability, cooling water, and backup systems. In regions where electricity is already constrained, grids already stressed, and environmental governance still maturing, the relevant question is who bears the cost, and whether what is being built now can be sustained.

None of this constitutes an argument against artificial intelligence. It is an argument for clarity. Treating AI as an abstract digital phenomenon obscures the fact that it is embedded in physical systems: grids, watersheds, urban air sheds, and therefore subject to their constraints. As inference becomes the dominant phase of AI’s lifecycle, the question is no longer whether AI consumes energy, but where, how, and at whose expense.

Understanding those trade-offs is a prerequisite for any serious discussion of energy, equity, cost-benefit analysis and long-term viability of AI. Without that understanding, the AI infrastructure being built today risks locking in costs that will be paid quietly, locally, and for decades.

Author’s note: OpenAI reportedly purchased tens of thousands of H100 GPUs (e.g., for clusters exceeding GPT-4's ~25k A100 setup), projecting roughly 10x the training compute of GPT-4. H100s deliver ~3x the performance per watt of A100s, so energy use is assumed to be scaled sub-linearly, potentially 3-4x GPT-4 levels, depending on utilization and overhead. (Semi-Analysis, Epoch.AI)

We spend hours researching and writing to bring you in-depth climate content. Consider supporting our work with a small donation. It makes a big difference!"

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0