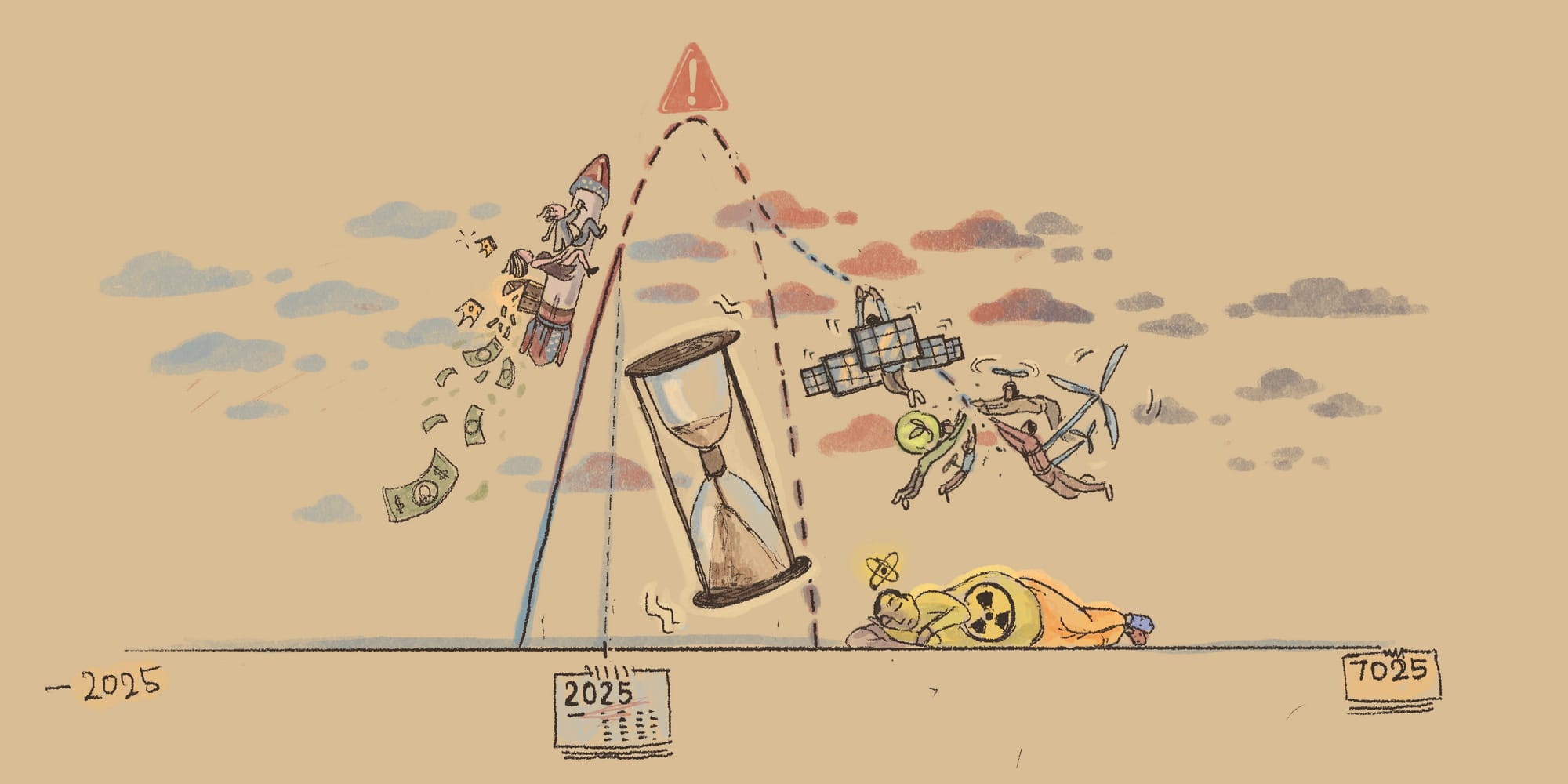

Spatial power density: Key metric to understand the energy transition challenges

Intuition on power output gap between Fossil fuels, solar panels and biofuels.

In my previous article on the global per capita power limit, I had had talked about spatial power density (SPD), which is the power delivered by an energy source divided by the land area required to produce it. In this article, we will look into why SPD is crucial when talking about the feasibility and limits of large-scale energy transitions, and I will attempt to develop an intuition for readers on why renewables (solar and wind) have lower spatial power density compared with fossil fuels, and why biofuels fare the poorest on this evaluation.

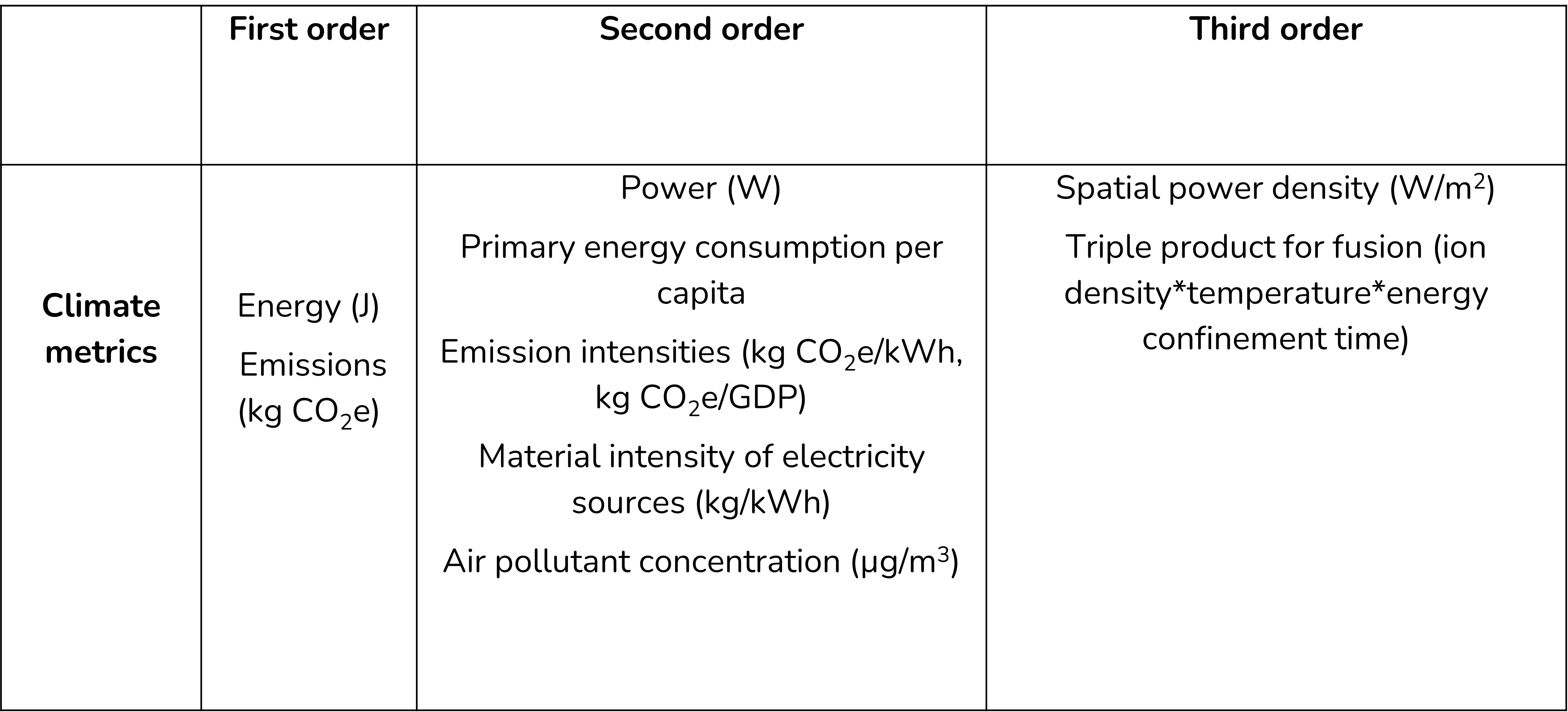

The distinctive feature of this energy metric is that it involves three variables — energy, time, and land area — and is therefore considered a third-order metric. Most metrics we encounter in climate discourse are second-order, as seen from the sampling in the table below.

Third-order metrics are especially useful because they pack more information into a single measure. The three variables they combine are both fundamental and often contested, making SPD a valuable ‘North Star’ for understanding the energy-transition challenges ahead. (If you know of any other third-order energy metrics, please share them; they deserve more attention on this platform!)

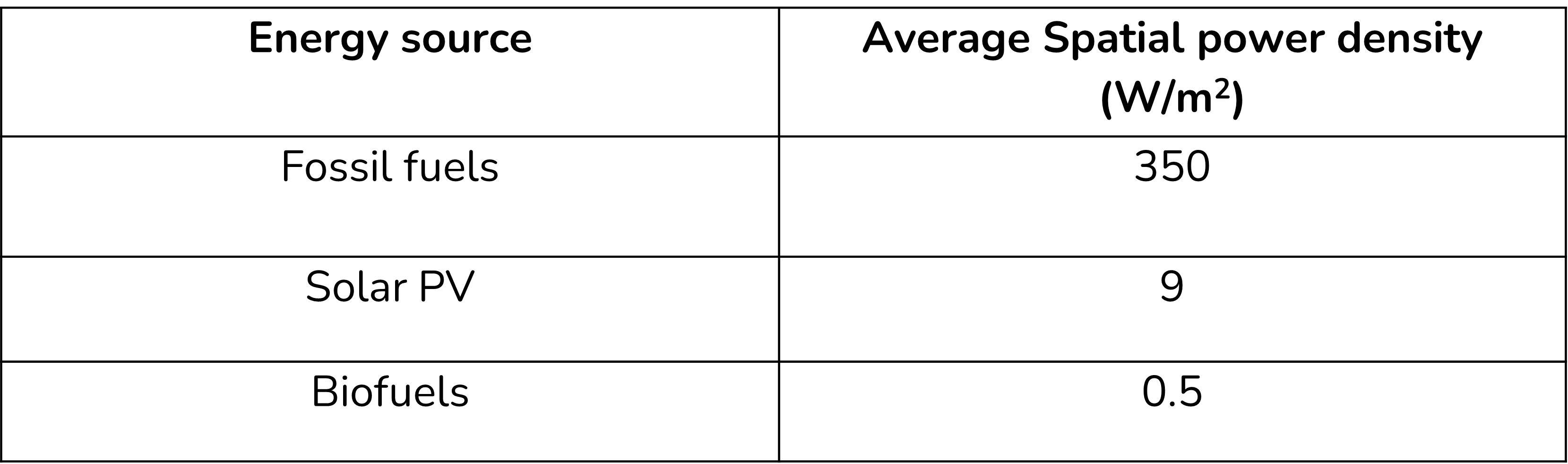

We have the SPD values for our three energy sources – fossils, solar and biofuels – in the table below (citations are provided in the Appendix). As you can see, the values differ by orders of magnitude. Let’s build some intuition on why these differences are so large and what they mean for our global low-carbon energy transition.

Fossil fuels vs solar panels

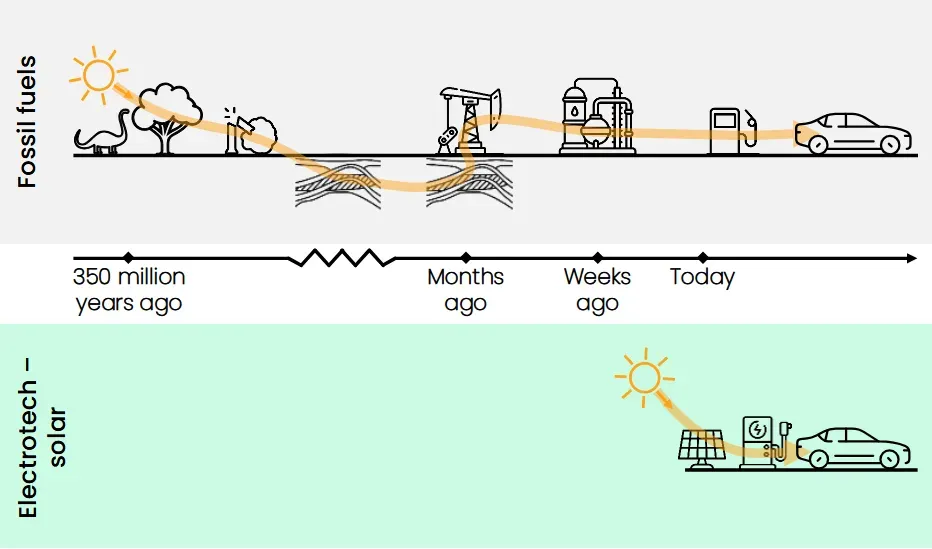

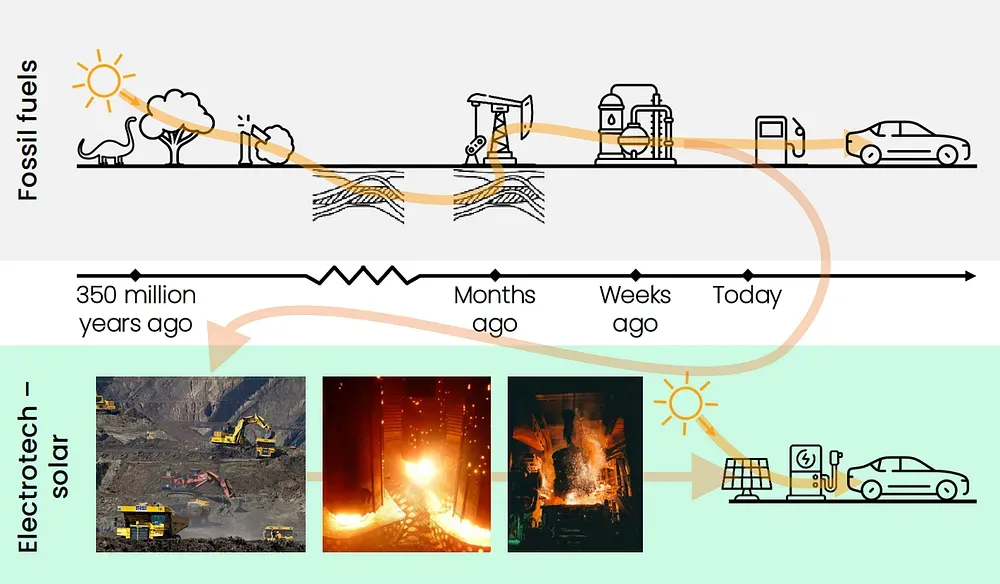

Recently I came across this post from the Honest Sorcerer, a popular Substack on energy transition and collapse, where the author talked how a simple illustration (shown below) comparing fossil fuels vs renewables can be highly misleading to the public when trying to understand the low-carbon energy transition.

At first glance, both panels seem perfectly reasonable. In the first, biological matter decomposes over millions of years to form fossil fuels, which are then extracted, processed, and delivered to the car at a gas station. In the second, solar energy is captured by panels, converted into electricity, and delivered to the car through a charging station.

The author then rightly points out that the second panel leaves out the substantial fossil fuel use involved in extracting and processing the rare earth metals and other materials needed to build solar panels. He follows this with a revised illustration that more accurately reflects renewables’ dependence on fossil fuels during their development.

Now, let’s take a look at another interpretation of the ‘incomplete picture’ in the original illustration. The key detail to notice is the reference to 350 million years ago. Ancient plant matter, which stored energy through photosynthesis, gradually decomposed, accumulated, and was buried under layers of sediment, heat, and pressure over geological time. This long process eventually formed fossil fuels. So, when we burn fossil fuels today, we are essentially releasing the solar energy that those ancient plants originally captured.

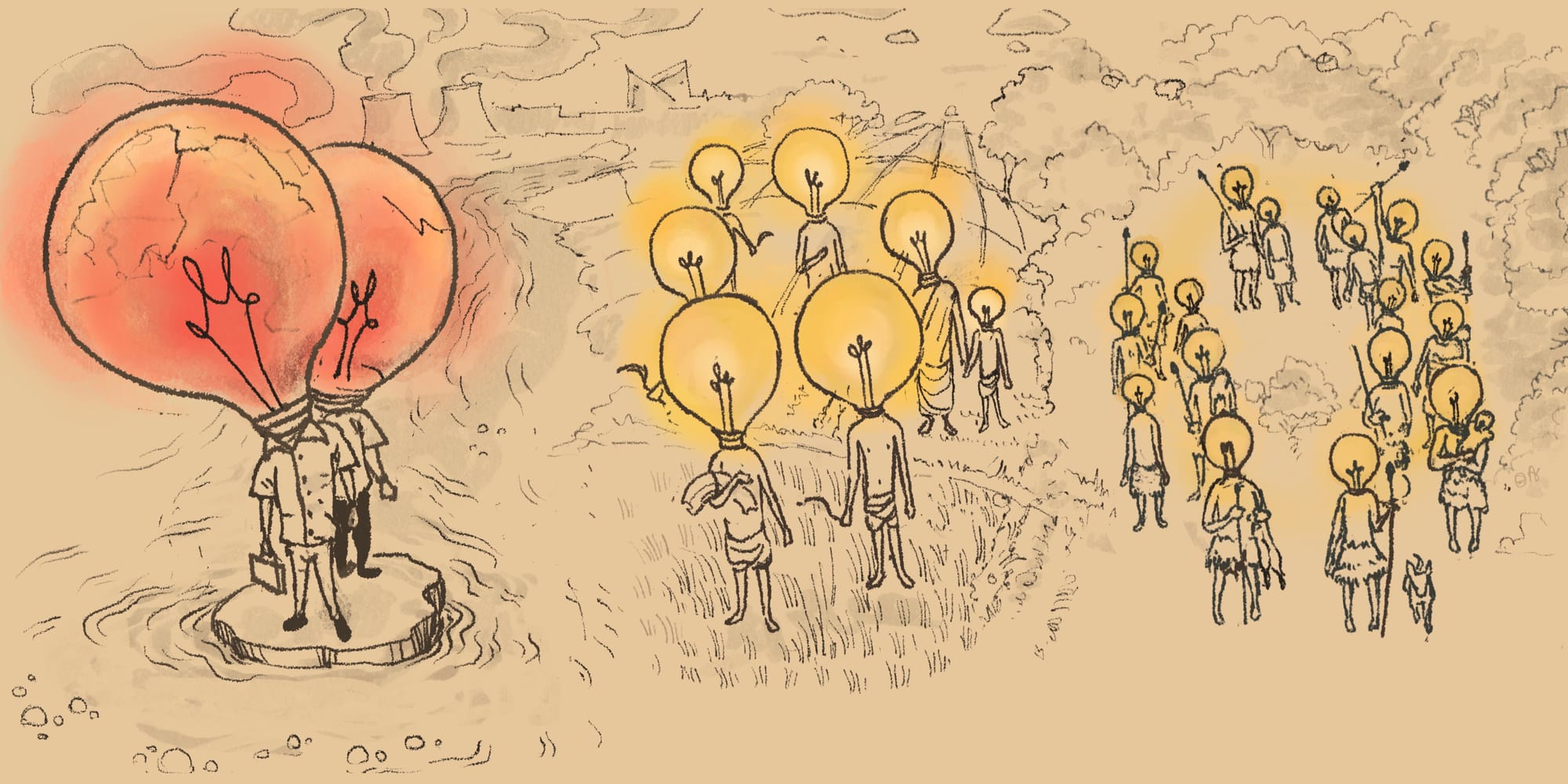

Hence fossil fuels are often described – rightly so – as 'ancient stores of sunlight'. In this context solar panels can be considered as 'human-engineered instant stores of sunlight' while photosynthesis can be considered as 'plant-engineered instant stores of sunlight.' Humans have been ingenious enough to create solar panels with an efficiency of 15–20%, far higher than the 1–2% efficiency achieved by plants through photosynthesis.

Naturally, these 'ancient stores of sunlight' will outperform 'human-engineered instant stores of sunlight' in terms of energy output. Fossil fuels had millions of years beneath the Earth’s crust to concentrate under ideal conditions, while solar panels are instantaneous energy processors with far less time and space to work with. When viewed through this geological lens, it becomes clear why renewables have a spatial power density two orders of magnitude lower than fossil fuels.

Furthermore, solar panels are also constrained by their theoretical efficiency limit (~32%) and by the intermittency of sunlight. So, while building solar panels (and wind turbines) is essential for the low-carbon transition, expecting them to match the energy output of fossil fuels is simply unrealistic.

Going forward, renewables will increasingly power our EVs; however, they won’t be able to match our current rate of energy consumption from fossil fuels, at least not at the current scale. Renewables can only continue to complement fossil fuels in the global energy mix. If we want to electrify our mobility and weave off fossil fuels completely, reducing our rate of energy consumption through private vehicles becomes inevitable.

To summarize, the illustration from Ember’s report (the figure above) overlooks the massive gap in spatial power density between the two energy sources. Yet, interestingly and somewhat paradoxically, it does implicitly reveal this gap through its mention of the 350-million-year timeframe.

To put it in more academic terms, expanding solar panels across land can never match the geological timescales and rich biological conditions that concentrated energy in the Earth’s crust and enabled fossil fuels to deliver such high power for our modern, industrial lifestyle. As humans, despite our ingenuity, we must accept that in some domains our industrial R&D — a few centuries old — cannot compete with Nature’s R&D, which has operated over billions of years. We simply cannot match the timescale advantage of natural energy-concentration processes.

And to make matters worse, we are burning fossil fuels in mere decades, far faster than the millions of years required for them to form, a clear sign of our long-term immaturity in using Earth’s energy resources wisely.

An article on energy security published in 2018 by Low Tech magazine discusses why renewables have markedly lower spatial power density. The following excerpt outlines their view:

"Although many media and environmental organizations have painted a picture of solar and wind power as abundant sources of energy (“The sun delivers more energy to Earth in an hour than the world consumes in a year”), reality is more complex. The “raw” supply of solar (and wind) energy is enormous indeed. However, because of their very low power density, to convert this energy supply into a useful form solar panels and wind turbines require magnitudes of order more space and materials compared to thermal power plants – even if the mining and distribution of fuels is included."

Solar panels vs biofuels

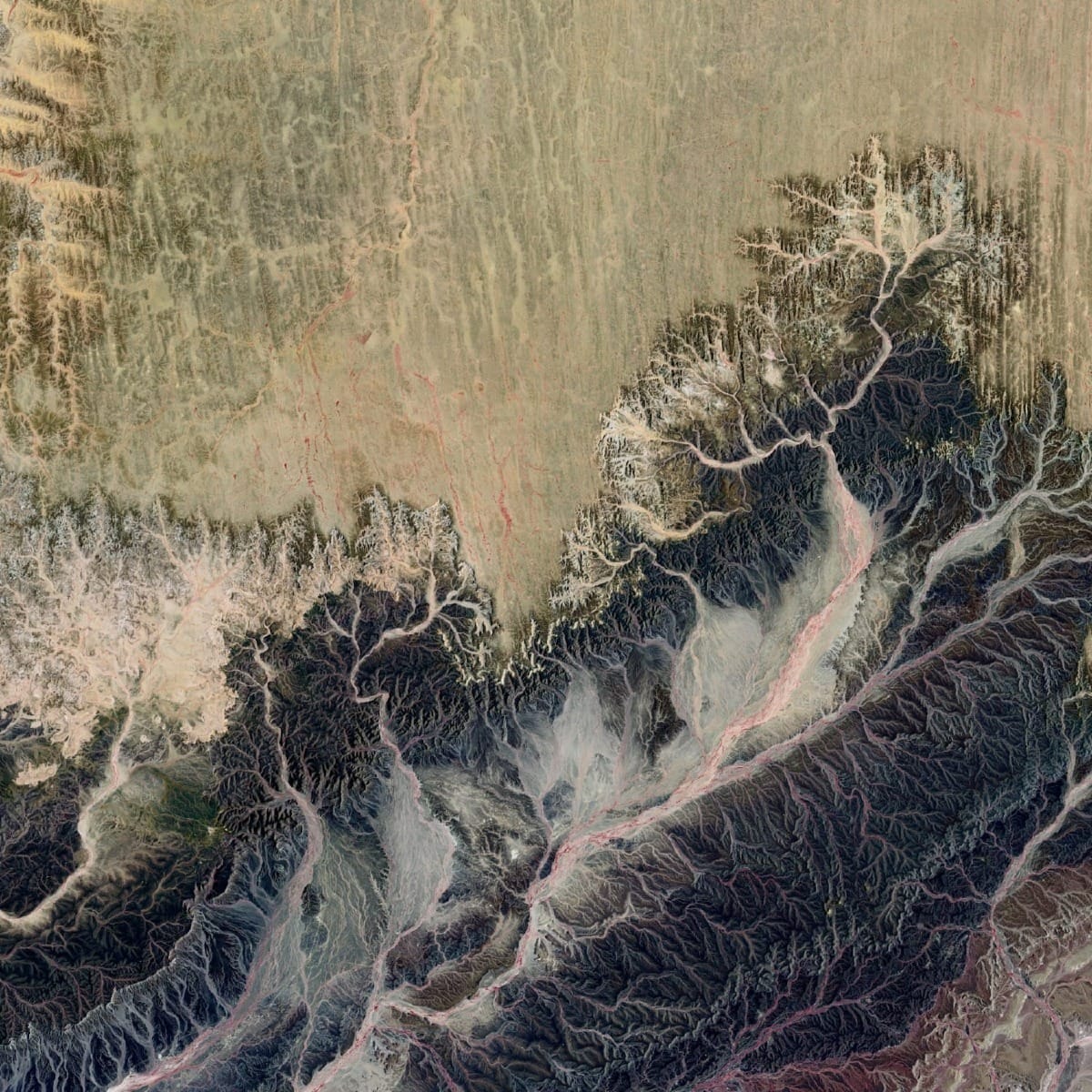

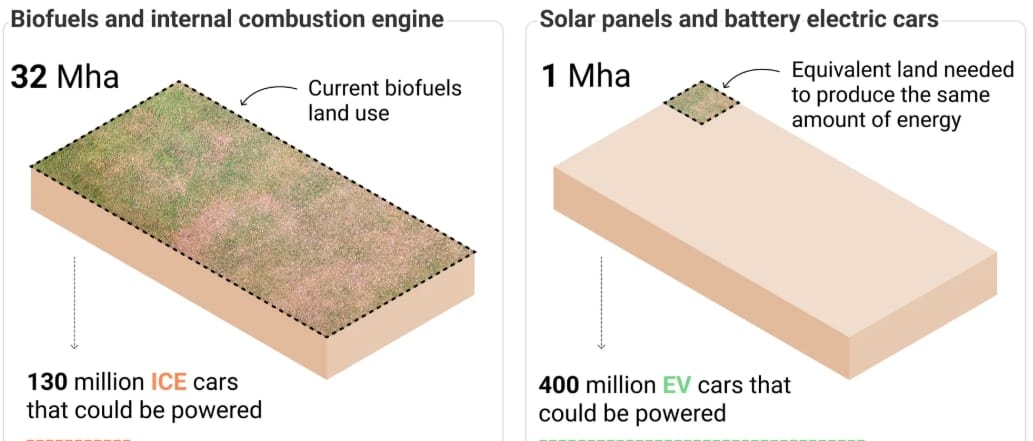

If solar panels struggle with spatial power density, biofuels fare even worse. Their limitations become especially clear when we compare how much land each energy source requires to power vehicles. A 2024 study by Cerulogy, a consultancy focused on cleaner fuels policy, visualises this contrast (shown below), and the results are strikingly unfavourable for biofuels.

To understand why biofuels perform so poorly on the SPD scale, it helps to look at how they are produced. Biofuel production typically uses corn stover — leftover stalks, leaves, and cobs from harvested corn — as feedstock, which is then processed through industrial hydrolysis and fermentation to produce ethanol. In essence, biofuels represent an industrial attempt to extract energy from an already low-concentration biomass source (remember, plants operate at 1–2% photosynthetic efficiency, whereas solar panels achieve 15–20%). In this comparison, the 'human-engineered instant store of sunlight' (solar panels) clearly outperforms the human processing of the 'plant-engineered instant store of sunlight' (biofuels) in delivering usable power.

Conclusion

Fossil fuels benefit from a geological timescale that compresses and concentrates biomass over millions of years, enabling them to deliver exceptionally high-power output. Solar panels and biofuels, by contrast, are instantaneous processors of sunlight, working with energy that is far less concentrated and fundamentally limited by efficiency constraints. This naturally results in their much lower spatial power density.

We would really appreciate your monetary support if you enjoyed reading this post and found it insightful.

PS: This article has been edited by Anjaly Raj.

For a deeper exploration of spatial power density, Vaclav Smil’s book 'Power Density: A Key to Understanding Energy Sources and Uses' is an excellent resource.

Appendix

The SPD values for fossil fuels and solar PV are taken from this research paper, while the value for biofuels is taken from here.